April 2023 Fighting erupts between the RSF and Sudanese regular army in Khartoum, sending thousands fleeing for safety. A third Sudanese civil war looks highly likely.

2011 South Sudan gains independence after a 49-year armed struggle that began soon after independence from colonial rule in 1956

In the dry season of 1983 I travelled from El Fasher in North Darfur, south and east, passing through Nyala, then towards the Nuba Mountains across the province of South Kordofan.

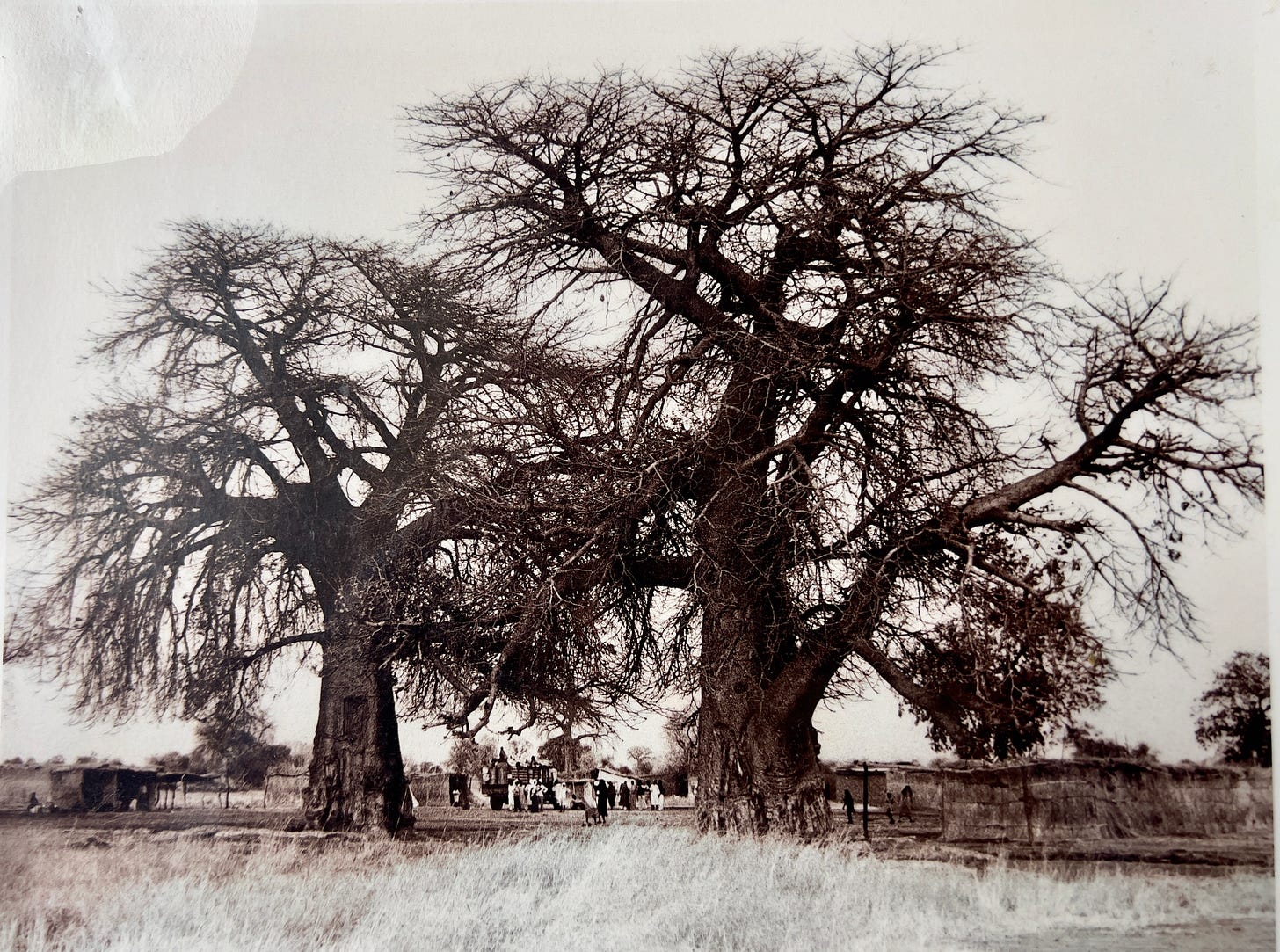

Somewhere in the long golden afternoon we pulled up at a small settlement in the vast open savannah. There were three giant baobab trees and a clutch of tin shack shops outside of which a few men were drinking tea. One of them, clutching a small bag, climbed up on the truck and found a place to sit next to me on the sacks of red onions. He was young, dressed in white shirt and black trousers, and I guessed he was a teacher, correctly as it turned out. Khalid was travelling home from the city of El Obeid where he taught in a secondary school. His English had a rather strange accent that I struggled to place until he explained that he'd been taught by Irish expats.

The lorry ground onwards, heading south-west along a red dirt track. There were acacia trees and occasional outcrops of smooth rounded granite, but there were no wild animals. "They are hunted," explained Khalid, "Very shy."

There were birds: hornbills, bustards and the occasional brilliant colours of a bee-eater.

Our transport was a souk truck, travelling like a tramp steamer from market to market, taking on and disgorging cargo and passengers. People held on to the sacks as the lorry lurched and rolled across the vast open swells of the savannah. In the cab were those who could afford to pay extra. The rest of us went up top, risking the possibility of falling asleep and being thrown off.

As an educated man Khalid was called on to tell any news he had of the world. His 'latest headline' was almost a year out-of-date, but no one seemed to mind. In Lebanon, he explained, there had been a massacre of 3,000 Palestinians by right-wing militias and the Israeli army. The bodies had been piled in the streets of the refugee camps. Word spread across the thirty or so people perched on the lorry, then down into the cab. One old man dressed in voluminous white robes had to have it explained several times, and when he grasped it, waved one hand aloft. "God help them. What a calamity! How can human beings do such things?"

Everyone agreed that it could never happen here, not in Sudan. The country was poor and beset with problems, but the people never did things like that. They were, of course, completely wrong about that. For centuries this belt of land had marked a division between Arab and African, Muslim and non-Muslim. European explorers had crossed it at their peril, disappearing southwards into the malarial swamps never to emerge. Arab war parties had traditionally gone there to collect slaves, and for that they were hated for that. In 1964, eight years after Independence, a group of Southern rebels, Dinka tribe mostly, had massacred a group of Arab nomads from the Messeria tribe.

But for the moment, here we were on a truck, all friends. And I knew almost nothing about that past, the one nobody wanted to speak about, or even admit to. I was a 22-year-old boy from the north of England and the worst sectarian violence I had witnessed was when a horde of Manchester United supporters had attacked a bus I was on. They didn't set it on fire and beat any escapees to death, however, they rocked it. And when everyone screamed, they stopped and ran off laughing. I had read Geoffrey Moorhouse's books White Nileand Blue Nile, both classics, and both full of gruesome incidents and horror. Those tales, however, largely involving men wearing pith helmets and braid, seemed unrelated to where I was. But, of course, they were not.

Khalid told me that he was a member of the Messeria Zurug, a semi-nomadic group who kept cattle, moving them between the savannahs of Kordofan and the lusher vegetation around a place called Lake Kailak. In this dry season that is where he expected to find his family, living in a temporary settlement of grass huts. He made Kailak sound paradisical: reed beds, wildlife and interesting people. "The Dinkas go fishing with spears in reed canoes. Sometimes the Fulani come with their cows from very far away - they say Nigeria, but I don't know if that's true."

He planned to borrow a bicycle in the next town and set off to find them. He laughed at my incredulity. "They always stay in the same area at this time of year. It won't be hard. I might cycle for two days, but no more. Why don't you come with me?"

I was actually enroute to Kadugli in the Nuba Mountains, but I swiftly decided that this was too good an opportunity to miss.

Night fell. The truck grumbled on, lurching and rolling. Eventually we pulled up a small town where there were a few paraffin lamps. Khalid and I got down. We slept on a pair of wooden benches on a beaten-earth verandah under a tin roof. The owner was an old Nilotic man with an impressive display of facial cicatrices, the ornamental raised scars that many tribes liked to advertise their allegiance. "Can you believe that this man was once a slave?" said Khalid.

The man nodded. It was true. He had been captured by another tribe and spent years working as a slave before someone told him slavery was illegal. Then he walked out. He still saw his former owner sometimes, in the post office in El Obeid.

Next day we borrowed two Chinese bicycles from the man and set off. I could tell we were heading south, but nothing else. We wove an unsteady course between the acacias. The land was absolutely flat without a single animate object in sight apart from the occasional hornbill flapping away. We carried no water or food. Khalid found some tiny bitter fruits that we gnawed on. Once we came to a hole in the ground that contained green water. "Can you drink this?" he asked, taking copious draughts himself. I was parched and drank deeply too.

Sometime towards mid-afternoon, he suddenly stopped, very alert.

"What is it?"

He looked anxious. "Too late, they have seen us."

I squinted into the scintillating whiteness ahead and saw a movement. There was a camel. Then I saw the tents: simple white shades.

"They are Hamar people," said Khalid, "They are brothers to us Zurug."

"You don't seem happy to see them?"

"No. But we must now greet them. Whatever happens, don't eat anything."

We cycled towards the tents. As we approached I could see the men rise from sitting around a small fire and spread out. One had an ancient muzzle-loading rifle, another had a spear. Khalid called greetings and they relaxed a bit, coming forward to shake hands in a long ritualistic exchange of pleasantries. We were welcomed around their fire. There were several camels browsing on the acacia, others couched down, their legs tied with plaited leather thongs. The men all wore sleeved tunics with a dagger secreted on the upper arm. "You will eat with us," said one, apparently the leader.

Khalid smiled. "Praise be to God, my friend, your invitation is kind, but we have only just eaten."

The man scowled and called out to the women who were squatted around a second fire twenty metres away. One of them rose and came forward with a large pot which she set down in front of myself and Khalid. I looked inside. There was the usual Sudanese staple, asir, a thick porridge, surrounded by a lumpy yellow sauce. The scowling man, our host, now moved behind me and suddenly barked: "EAT!!"

I jumped. Khalid was staring at the pot.

"IN THE NAME OF GOD, EAT!!"

My right hand crept forward, took a scoop of porridge and dipped it in the sauce. Khalid still did not move. I put the food in my mouth.

"Al-Hamdu-Lillaah!" exclaimed our scary host, turning to Khalid. "EAT!"

The sauce had a bitter but not unpleasant tang. I realised I was incredibly hungry. My hand started moving faster. Tentatively at first, Khalid also began to eat. In the end we ate a lot, although careful to leave plenty.

At a shout, the woman came and took away the pot. I was just thinking: 'Thank goodness that's over', when a second woman came forward, with a second pot. The scowling man was replaced by another. As the pot touched the ground, this fresh host leaned forward, right behind my ear. I could feel his breath. When the shout came, it still made me jump. "IN THE NAME OF GOD. EAT!!"

This sauce was tastier. His wife - I assumed - was a better cook.

When the third pot came, I could hardly take more than a mouthful, despite many orders to EAT!!

At last we were allowed to sit back. A tiny glass of thick sweet tea was served. It did not taste like any tea I'd had before. Then we watched while our hosts ate. Once that was done, the pots went to the women and children.

I asked to see their tents and was shown around. This was the simplest and most austere of lives. Each tent was held up with slender poles. There were a few grass mats, some saddles of exquisite and much-used leather, then a few leather bags. Even their water was stored in leather bags. A sword hung in a scabbard. I asked to take photographs, and they agreed, asking to see the results - which was impossible in those days. I offered to send prints, but Khalid chuckled. None of them had an address, or even understood what it meant. They asked if I knew the white men who lived inside the spaceship near the Bahr al Ghazal river. A little questioning revealed that, in their wanderings, they had come across a sumptuous living capsule, probably a caravan, in the middle of nowhere. The white men had been friendly and shown them inside. They had electric lights, soft chairs and a box that lit up when you opened the door and was cold inside. During the day they were drilling holes in the ground. They were, I realised, an oil exploration company.

By this time, the initial frostiness of the men had entirely disappeared, but Khalid was keen to go. After a few more minutes, amid hearty handshakes and declarations of friendship, we departed on our bicycles. As soon as I could, I asked Khalid why he had told me not to eat anything. Had it been that he did not want to be in their debt? Or suspected poison? Or something else? But Khalid was evasive.

We cycled into the gloaming, then darkness. It became cold and we stopped to build a fire from twigs and dry camel dung, then lay down next to it. Khalid pointed out the stars and named them in Arabic. His father had sent him to the town to be educated, much against his will. It had not been easy. Once he had been invited to eat at a European's house in El Obeid. "Each person had their own food on a plate," he told me in a horrified voice, "Nobody shared. Is that normal in your country?"

"Yes."

He groaned. "I seek refuge from Satan!"

The dinner had not gone well. "They ate with knives and forks - never touching the food. I couldn't do it. In the end, I threw away the knife and fork and used my hand like a civilised person."

And the food itself?

"Horrible. Worse than the food of the Hamar people."

I grinned to myself. Overhead the stars seemed to quilt the heavens and hang lower. The air grew colder and colder. When I woke, it was dawn and I was shivering uncontrollably.

[to be continued]

What adventures you have had! Thank you for sharing them here