January 2024 Missiles are fired at ships in the Red Sea from Houthi-controlled Yemen

April 1994

Sana'a central jail is not a place to find yourself, not as an inmate at least. I had gone there to visit someone, an expatriate who had been cheeky to a customs officer at the airport. Unfortunately the cheeky comment led to a search and the search uncovered what the Yemenis described as pornography. A judge watched the two videos and agreed, passing a four-year sentence. I have no idea how shocking those videos might have been, the judge may have kept them.

The jail had something of the medieval castle about it. I passed through various gates of ancient iron with huge locks and dark passageways before emerging in a large courtyard, the place where the prisoners congregated. When he appeared, my expat inmate looked tired and harassed. The system, he explained, was that all the prisoners organised themselves and were supplied with food from their families outside. Big tribal leaders became big convict leaders and were surrounded by henchmen. He was surviving in a state of constant fear. "There's lots of murderers and rapists," he said. Many of his fellow prisoners were undoubtedly insane. Violence, intimidation and bribery were endemic.

We chatted for a while. I gave him a pack of Kamaran cigarettes and some qat leaves to chew. Looking around I could see that not everyone was an unshaven murderous lunatic. There were men who appeared to be coping. They had clean clothes and looked well fed. Some had an air of importance. I asked a guard who they were as I was leaving. "They are the sons of tribal leaders," he told me, "Kept here so their fathers behave themselves."

This was the system. Yemen has many mountainous regions populated by fiercely independent tribes, some of whom had never fully accepted the victory of the Nasserite socialists against the royalists in the 1962-70 civil war. The king of North Yemen, Imam Badr, had fled to Britain and was living out his days in genteel retirement in Kent. Many of these tribes lived along the undefined border with Saudi Arabia. They shared the old king's religious affiliation with what then seemed like a rather obscure branch of Islam called Zaydism.

At a qat session some days later I mentioned my experience at the prison and asked about those hostages, kept to keep the tribes in line. Someone mentioned that there was a relative of "al-Huthi" in the jail. It was the first time I had heard the name applied to a person, but I knew the place from where it was derived.

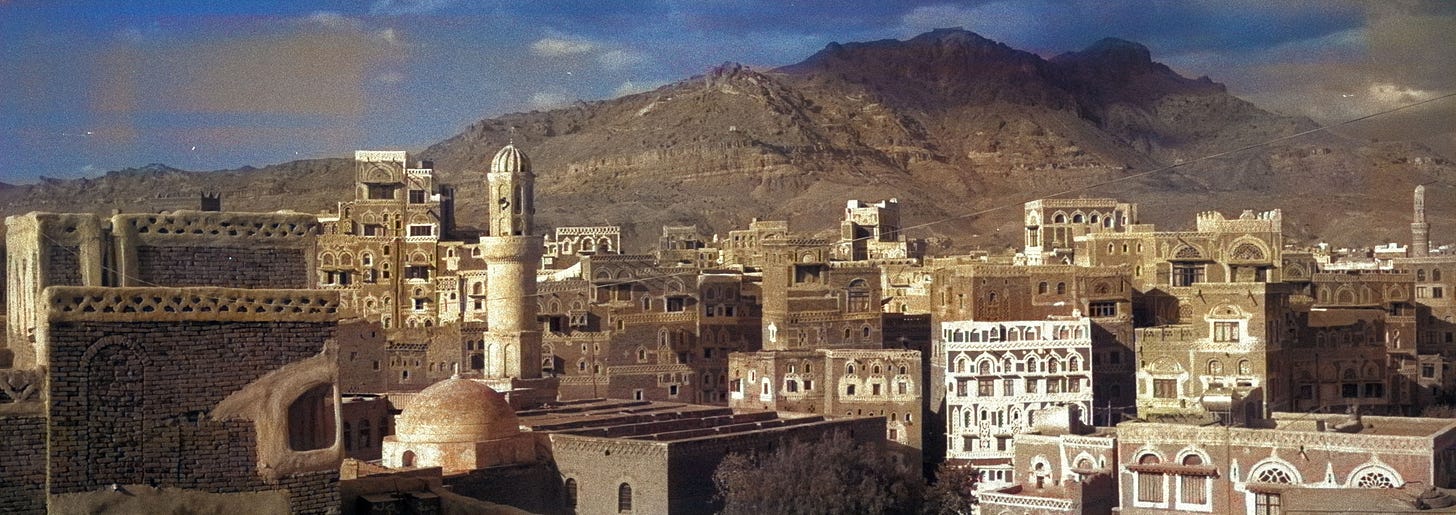

I had been to Huth a few times in the late 1980s. It lies on the road from San'a to Sa'da in the far north of the country close the Saudi border. We pulled in, hoping to find a restaurant. The houses were tall mud and stone towers, several in ruins, leaving the village with the appearance of a being beach sandcastle that has been attacked by older boys There was one restaurant, a tiled cavern that had obviously never been cleaned since it opened. In one corner a man was dishing up the lunchtime special from a huge aluminium pot: chunks of yellow meat in an oily broth. There were a few metal tables, but many diners chose to sit on the floor or outside on the step. Most looked like they were passing time before robbing a bank, except that Huth had no such facilities. The entire place looked exactly as the rest of Yemen perceived the Zaydi north: as a region filled with uncouth bumpkins who liked fighting.

We were given a bowl piled high with yellow meat. And then, just as this was about to become the worst lunch ever, a smiling man came over and delivered some flatbread from the tannur oven. It was warm, flaky and utterly delicious. "From the lion came forth sweetness," said someone, quoting from the Golden Syrup tin. When we finished eating, another diner bought us tea, waving away any idea that we might pay. I washed my hands under a filthy dribbling tap and set off to walk around the village.

Huth had clearly never benefited greatly from participation in the nation state of North Yemen. It was dilapidated and unloved. Most of the men could only hope to make money by exporting themselves to Saudi Arabia for several years where they could work as building site labourers or security guards. They would, during that time, learn to absorb many insults and indignities. At home in Huth they might think of themselves as proud independent people, but in Saudi they were a hairsbreadth above being slaves. With luck they would come home with sufficient cash to get married and build a house. It could take many years.

The Yemeni population here were Zaydis, the form of Shia Islam that reveres Zayd bin Ali, a great grandson of Ali, the first successor to the prophet Muhammad. Zayd had revolted against the Umayyad caliphs in 740, claiming they were corrupt and dishonest. The rebellion was crushed almost immediately, and Zayd killed, but his reputation as an honest man fighting for justice in a bad world survived and attracted followers who went on to found dynasties in Spain, Iraq and Morocco. None of these survived, except for one small enclave in North Yemen. From that community had come the Mutawakkilite dynasty who took over from the Ottomans in 1918 and ruled until civil war broke out in 1962.

After the Mutawakkilites were deposed, the region around Huth did not prosper. My post-lunch walk showed that. This was a place where money was tight. Battered old Landcruisers parked next to mounds of rubble and a group of badly-nourished children, barefoot and with wind-chapped faces, shouted at me. "Ya Kuri!" They had decided that I was Korean, an ethnicity for which I am rarely mistaken. Not many outsiders came here.

In 1991 Yemen chose to support Saddam Hussein against the American-led coalition and Saudi Arabia abruptly terminated all work visas for Yemenis. Around 800,000 were forced out. In Sana'a people got used to seeing gilded youths in sports cars breaking their axles in potholes. They had stylish haircuts and sleek Western clothes but they were a small percentage of the total, most were hard-scrabble workers who had lost their only realistic chance at getting some money together.

Soon after this cataclysm, one particular inhabitant of the area around Huth, Hussein al-Houthi, began to preach a Zaydi renewal. At first his followers were a handful of family, but slowly it grew into a movement, powered by poverty and regional marginalisation. Their goals were to revive Zaydism, fight corruption, and to counter foreign involvement in Yemeni affairs.

In Huth that day we downed a glass of sweet tea, and set off for Sa'da. En route we took a diversion to visit two villages of Yemenite Jews. There were a few hundred people who had resisted all the blandishments of Israel and chosen to stay. As far as I could see they looked like all other Yemenis except that the men wore two long forelocks of hair in front of their ears.

From here we drove further north, staying a night in Sa'da before heading towards the Saudi borderlands. I wanted to see a market I had heard about where weapons were openly sold. After asking directions several times before finding Suq al-Talh: a dusty area surrounded by low rocky hills where a few beige-coloured Landcruisers were parked outside some tin shacks. I walked into one and found a man sitting at a desk with a display of pistols on the wall behind him. There were some antiques among them that looked like relics of the Wild West, but there were Czech and Israeli arms too. He seemed quite ready to sell me one of them. I asked about Kalashnikovs and he gave me various prices. Did I want a Russian original or maybe an Iranian copy? If they were too expensive there was always the cheap Chinese version. Or was I after something with a bit more power: a bazooka, perhaps?

With my tongue firmly in cheek, I said, "What about a tank?"

He laughed, shaking his head. "Oh, no. That is a special order. I need two days for that." I couldn't tell if he was joking.

By 1994 when I visited the prison in San'a, the Houthis were still not a powerful force but that would change (that spelling of the name seems to have become standard). In 2004 Hussein al-Houthi was killed by the Yemen army and his brother, Abdul Malik, took charge. The movement that had started as a religious revival now became a full-scale rebellion. By 2014 they had taken San'a, triggering Saudi Arabia to intervene and start the ongoing war. With UAE and Iran also involved, plus weapon supplies from Britain and USA, foreign intervention in Yemen is at an all-time high. Laser-guided missiles, drones and high explosive shells are the new order. Suq al-Talh no longer exists and, relative to now, seems like part of a lost age of innocence.

Back in May, 1994, the awkward reunification of North and South Yemen that had happened in 1990 disintegrated into war. For Yemen it was yet another disaster, but for one expatriate inmate of San'a prison it proved fortuitous. He was released and deported.

Imam Badr, the last king of North Yemen, died in 1996 and was buried at Brookwood Cemetery in Woking. He shares his resting place with a richly cosmopolitan array of notables including Horatio Nelson's grandaughter, the thriller writer Dennis Wheatley, the architect Zaha Hadid, and Marmaduke Pickthall who translated the Quran into English. Al-Badr was said to be a kindly and courteous man. His attempt to regain his kingdom during the 1962-70 war had initially gone well, but came to a sudden end when his main backer, Saudi Arabia, abruptly changed sides.

2004 Afghanistan.

Finally my hopes of owning a tank are realised. In a breakers’ yard in the hills near Kabul, the supervisor gives me an antique Russian T54. I decide against driving it home, but remove the gun sights as a souvenir.

Brilliant as always