Burma 1988

28 March 2025 An earthquake measuring 7.7 hits Myanmar and Thailand, killing over 1,000 people and injuring thousands of others. As I write the true extent of the damage is unknown and perhaps never will be as much of Myanmar is in a state of civil war. The struggle against military dictatorship has been ongoing for decades, ever since General Ne Win grabbed power in 1962. A crucial turning point came on 23 July 1988 when Ne Win resigned and, for a brief moment, hopes grew for a democratic government.

July 1988 Travel to Burma was limited to a one week visa and the only visitors were backpackers. I flew into Rangoon with my ex-wife, Judith. Our two main objectives were to see Lake Inlé and the ancient city of Pagan (now Bagan), a site often damaged by seismic disturbances (although it seems to have escaped relatively unscathed this time).

The train north from Rangoon was a clanking, super-slow, service. All the backpackers, mostly Aussies, were herded into one carriage. I fell asleep sitting on a wooden bench, then woke crouched in the aisle shouting, "I'm trapped in the rhythm of the train!" I cannot recall what the nightmare was, but I do remember all the faces staring at me. With a muttered apology for waking everyone, I reseated myself.

After staying on Lake Inlé, we went north to the town of Taunggyi, spending one night there. In the restaurant we sat down at a table with a neat white tablecloth only to notice that a column of ants was marching across the centre. Closer inspection revealed that they were coming up one table leg and down another. During the entire meal, the waiter took pains to avoid squashing any of them, placing the food with great care. I admired his concern for nature.

Next morning in the market I found more cash by the simple expedient of changing a US$100 banknote into ten $10 notes. That might seem an unprofitable manoeuvre except that $100 notes were in demand and dealers were prepared to add a significant pile of Burmese kyat in order to get the coveted larger bills.

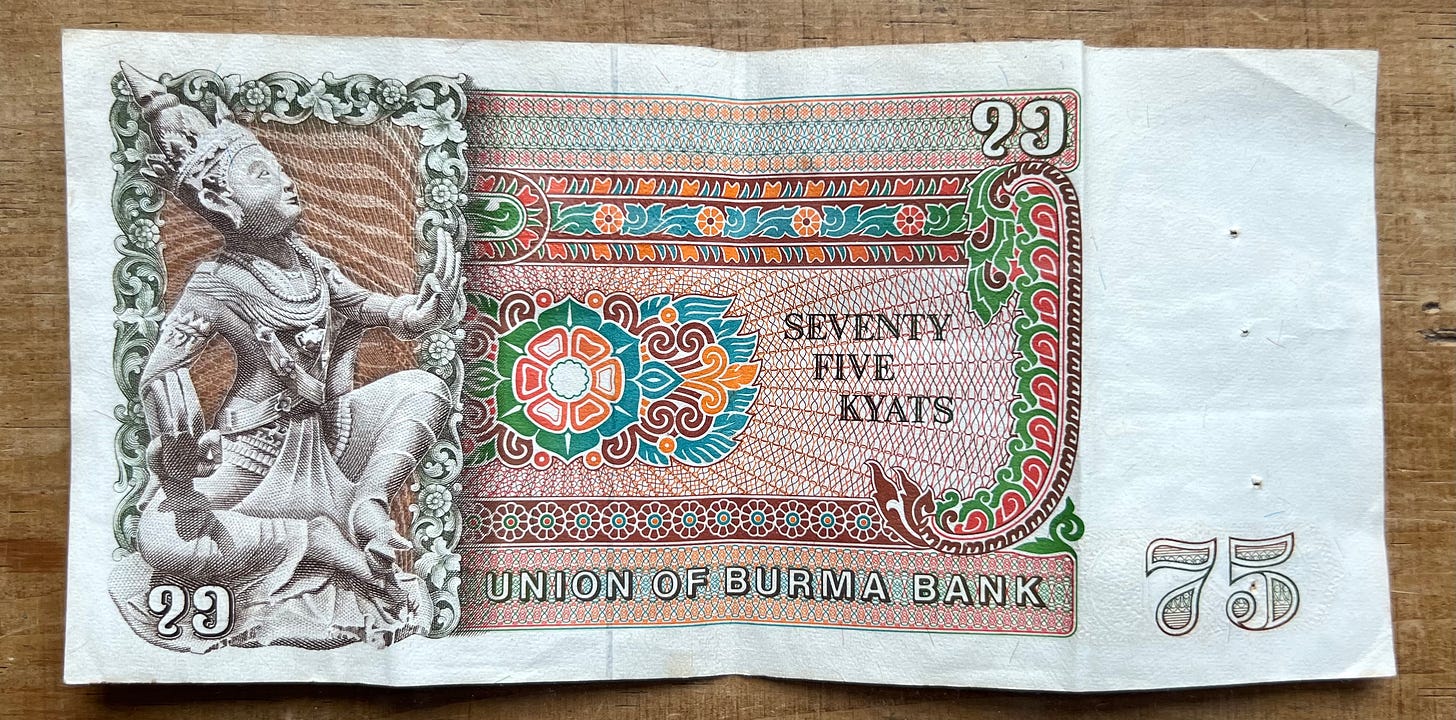

Money was a hot political topic. The government had recently declared that the 25, 35 and 75 kyat notes were no longer legal tender and instead introduced the 45 and 90 kyat notes. These numbers were said to be the favourites of the military ruler General Ne Win. In that draconian act they put about three quarters of the country's money out of circulation and destroyed the savings of millions of its citizens. Walking through the market we fell into conversation with a neatly dressed old lady who invited us back to her house for tea.

The house was a tidy wooden bungalow of simple furniture dressed with antimacassars, white lace cloths hung over chair backs and arms to protect them from the hair oil that everyone used. In one corner was an upright piano. Our old lady was a music teacher and over tea and biscuits she poured out her sorrows. Her son was a student activist in Rangoon. "It is terrible what is happening," she said, "The students are hungry, but when they went out to protest, the soldiers grabbed my son's friend and smashed his head against the paving stones. He died."

We sat there stunned. In that tranquil, civilised house, her words seemed all the more chilling. We had stayed in Rangoon a few days earlier, drinking gin without tonic - 'Sorry Sir, unavailable' - at the famous Strand Hotel. Neglected and rundown, the historic bar was alive with cockroaches which no one would kill. If there had been any sign of unrest in the streets, we had missed it. Now all we could offer was condolences and the hope that her son would be alright.

Later, the old lady walked us back to the market and located our transport for the onward journey to Pagan.

In a corner of the marketplace was the taxi, but this was no ordinary vehicle. The battered Willys jeep had been left behind by the Americans at the end of WWII, then converted into a bus with an extra structure on the back equipped with bench seats. Between these, down the middle, was a row of wooden stools. Fortunately we were first and, congratulating ourselves, took the front passenger seat. We could share.

The back filled up with people and their purchases. Our delight at having the front seat soon ended: two more passengers squeezed in. I was now pushed almost on top of the driver. How was he going to operate the jeep? The dashboard contained an empty space for a missing speedometer. Rusted wires protruded where once had been switches for non-essential equipment like headlights. Next to my thigh, the innards of the gearbox gaped up at me through an oily black hole.

Eventually, with 26 people aboard, the taxi was declared full. The driver got in, beaming with happy smiles and carrying a curiously shaped stick. With a deep cough and a noxious belch the engine was started. Our driver took his stick and with a great theatrical flourish, shoved one end into the hole next to my thigh. There was a sickening crunch then the jeep gave an exhausted spasm and lurched forward. Teams of onlookers sprang into action, shoving us onward. The engine retched horribly but kept going.

Soon we were rolling along rough country lanes, occasionally bashing through overhanging stands of bamboo and vegetation. Every now and again the driver would take a hopeful stab at the gears while keeping one hand busy on the steering wheel, twisting it this way and that, without any apparent effect on the direction of travel. At every lurch I had to brace myself against the other travellers and keep well clear of that menacing black hole. I had the firm conviction that if any part of my anatomy fell into that diabolical gearbox, I would get pulled in, probably to be spewed out the exhaust pipe as hamburger meat.

And then it began to rain.

Of the next few hours I have only painful memories. The times when we sank into mud and had to get out and push should have been a relief, but the tropical downpour was so heavy it seemed impossible that so much water could fall out the sky. The driver, however, never once stopped grinning and waving his magic gear wand.

Seventeen hours later, at dawn, we pulled into Pagan and all the pain and fatigue was suddenly gone. Steam was rising from the jungle and above it, touched by the first rays of sunlight, was a forest of temples and pagodas. We wandered around in an exhausted daze, astounded by the decorative panels and reliefs: the Buddha in blissful full lotus hovering above a stupendous assortment of flowers and vines; goggle-eyed gargoyles snarling from cornices; dancing nymphs brandishing peacock feather fans. It was overwhelming. I was shattered. At the first available guesthouse, I was asleep before my head hit the pillow. It felt a bit oily and I remembered, with regret, that civilised old piano teacher with her crisp clean antimacassars.

*

A few days later, having landed back in Bangkok, the news came that full-scale riots had broken out in Burma. The 8888 rebellion, named after the date it began, did not go well for the protestors. Demonstrations were brutally crushed by the military dictators with thousands of deaths. The following month Aung San Suu Kyi founded the National League for Democracy, but she was soon placed under house arrest. Burma had not been a happy country since General Ne Win took over in 1962. His policy of self-sufficiency and high tariffs had led to isolation and stagnation, but now it began to slide into the terrible violence and chaos from which it has yet to emerge.

© Vyacheslav Argenberg

You’re back!

I, too, have awaited your return! Couple of thoughts that have less to do with the eloquence of your prose and more to do with daily reflections on the weight of this crumbling world. It's odd to perceive indifference in Buddhist manners. Something seeking religious purity seems a tad bit impotent in its disregard for the welfare of man. The other on the monetary policy of withdrawal of currency: No one in America has even questioned the government's intention to discontinue the penny. I doubt they will be offering a return on the collective value; certainly not for consumers. I'd be surprised. Peace out, Kevin. PS: I think about Aung San Suu Kyi often, to this day.