Do The Techno

two steps forward, one to the side, then one back

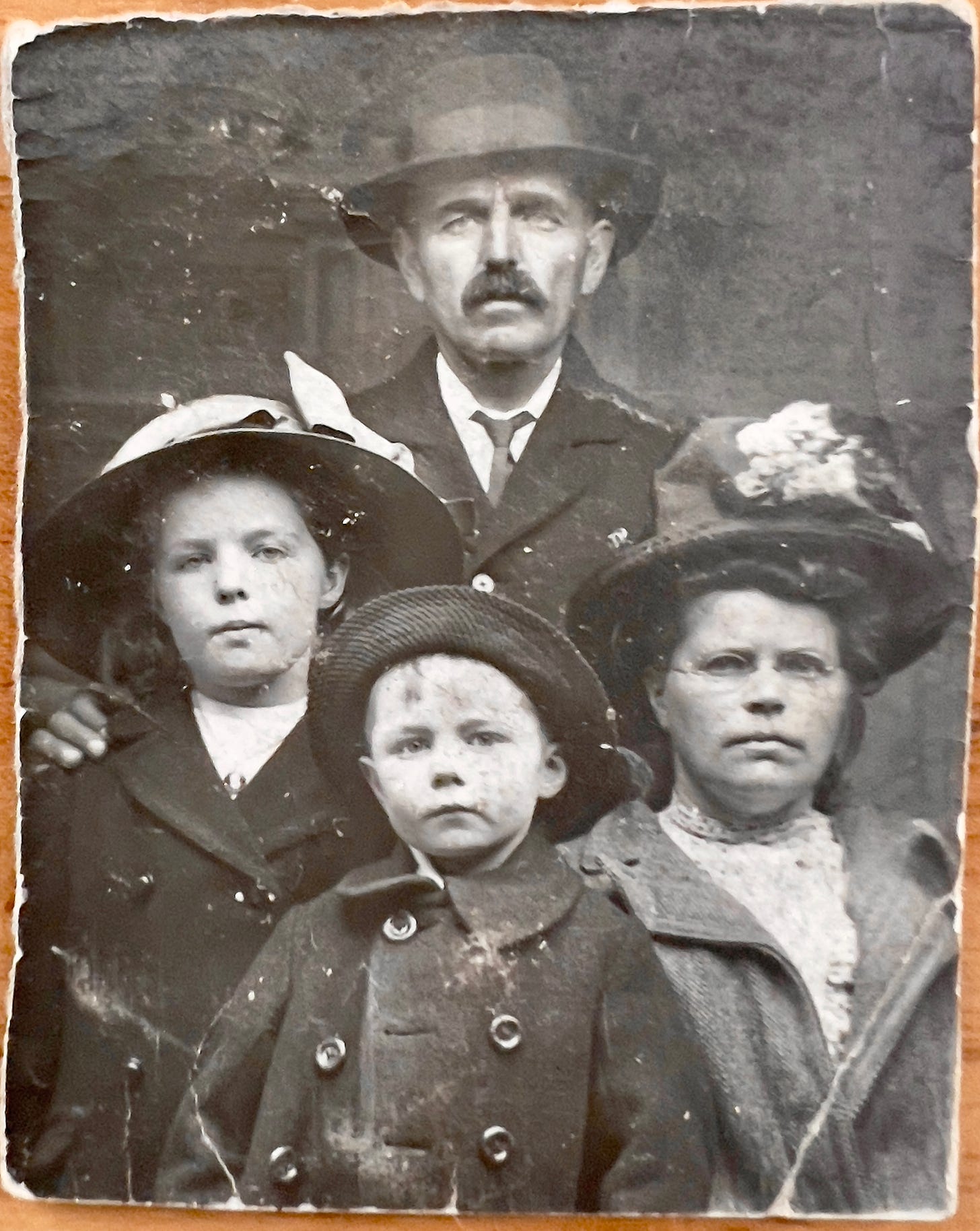

My mother is in hospital and I'm camping out at her house. In a wardrobe I discover the first camera I used: the Mamiya mentioned in previous posts. And then my eye is drawn to an old tin that I open to find a treasure-store of old photographs. Black and white prints, sometimes sepia, faded and often undated. Sometimes there is a scrawled message on the rear, just the names. The poses are formal. They were taken in photo studios in Lincoln and Market Rasen, the subjects in their Sunday best clothes staring squarely at the camera. In those days people were told not to smile: exposures were so long that no one could sustain happiness long enough. Children, of course, were used to being ordered to keep still and silent. Despite all that is lacking - colour, emotion, normal life - these images speak eloquently of lives lived a century ago.

You can see that my great grandfather, William, was not a man to cross, and you can also see that his wife and daughter may have learned this. My great uncle Fred looks about four, dating this picture to around 1916 which may explain the hint of wistfulness in William’s face: his other son, my grandfather George, was in the trenches at Ypres. He’d lied about his age and was just 16 years old. My mother, currently in a hospital bed, is remembering things that I’ve never heard before. “George would never talk about the war,” she says, “When your Dad asked him, he said that all he could remember of Ypres was crying for his mother.” That lady obviously had a softer side than the one shown here.

Two years later at Cambrai, now a cannon-fodder-legal 18 years of age, with his Lewis machine gun red-hot from spewing rounds, George took a faceful of phosgene gas and went blind. All this I piece together from an envelope of letters and a notebook, also in that tin. As a writer I always like to say that a well-kept notebook will trump any selection of photographs, but in this case I'm not so sure. Grandad George wrote in pencil which has faded and he never wrote anything remotely interesting, except perhaps when he complained, "Two of the eggs you sent were broken, but the cake was good."

We assume that technology makes everything better, but I am sure I could not successfully send a dozen raw eggs to a soldier at the front in Ukraine. Technology makes fortunes for a few, that's all. Some gadgets may increase the sum of human happiness, but we humans like novelty, and are always prepared to believe the silver-tongued snake-oil shyster. Colour photography was a step forward, but in abandoning black-and-white we left something behind too.

I started out developing negatives and prints in my mother's attic in the late 1970s, using very basic equipment. But in 1996 some new kit unexpectedly fell into my hands. It was extremely high quality and came with a story attached.

Pat and Carolyn Whitaker lived in one of the finest houses in London. It stood on a bend in a road in Primrose Hill and was painted lemon yellow, "Just to annoy the neighbours," Pat used to say, but he was joking. Pat had a twinkling charm and it was difficult to imagine him ever annoying anyone. The street will be familiar to fans of the Paddington Bear films where it is home to the Browns who adopt the ursine immigrant. You catch glimpses of what was once Pat and Carolyn's house, standing in pride of place on a gorgeous curve of Georgian real estate, still daubed in the lemon yellow that Pat had first covered it back in 1956 when he bought it. "He was robbed," Carolyn would say, chuckling. "£1200! It seemed like madness." Nothing in that street goes for less than several million these days.

By the time I met Pat he was already an invalid. I never saw him dressed in anything but an old-fashioned dressing gown, the sort Paddington Bear would like. Carolyn ran a literary agency called London Independent Books and she had become my agent in 1995. They seemed both impossibly grand and wonderfully earthy, relics of a bygone era, a bohemian 1950s lifestyle that embraced jazz, cocktails, and polished mahogany speedboats, but also Heinz salad cream and corned beef. Lunch at their house always seemed to hold the possibility that Noel Coward might breeze in, airily wafting a cigarette in a holder and demanding that the crusts be removed from his potted shrimp sandwiches.

Pat was a great fan of Frank Sinatra. In the 1950s he had been stuck in Las Vegas for a week and the only show in town was Ol’ Blue Eyes at the Copa Room in the Sands Hotel. Pat went along reluctantly, never having liked the singer, but after the first show he was hooked and went every night. The audience was a celebrity roll-call of the period: Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall and Sammy Davis Jr. all coming down for a drink with the Mafia’s favourite crooner.

Pat liked a drink too. He was a cameraman with Pathé, shooting stories for their cinema output. Before most homes had television, visual news appeared in short reels before the main feature film. For the cameramen, there was always plenty of waiting around and during that time Pat would sit in the bar. "He never got drunk," Carolyn would say, "But he never stopped either, and it all added up."

Unfortunately for Pat it added up to a complete physical collapse followed by an endless convalescence. Carolyn had an office in Bayswater, but she'd often pop back to Primrose Hill for lunch and to check on him. We would squeeze on their tiny balcony and nibble on a few bits and pieces, side dishes for the main course, which was a bottle of wine followed by a Capstan Navy Cut cigarette, a real ‘lungbuster’ as they were affectionately known. Pat would also keep a can of extra strong lager going throughout, discreetly tucked down by his slippered foot.

His career with Pathé had started soon after WWII ended. By 1955 Pat was on hand to film the spy Kim Philby, denying allegations that he was the 'Third Man'. A year later, when Soviet-leader Nikita Khruschev met British prime minister, Sir Anthony Eden, Pat was there recording it, before dashing off to catch Miss Ghana who was touring London. He witnessed the first race riots in Notting Hill, numerous FA Cup finals, air disasters and rail crashes. He filmed the launch of the first-ever floating oil-drilling platform and visited The Cavern in Liverpool to cover the emergence of a new band called The Beatles. When the first commercial jet aircraft, the Comet, went into service in 1959, Pat flew round the world in 80 hours. There were innumerable royal tours, the kind that featured royal personages wearing silly shorts, standing in open-top LandRovers and waving to cheering locals, also in silly shorts, waving clean hankerchiefs.

That day I'd gone, as usual, to lunch. Pat and I sat on the balcony while Carolyn prepared the food. We got on to the subject of mobile phones. Would they catch on? At that time, the 'mobile' was as heavy as a lead brick and needed a car to transport it. Carolyn still answered their phone like an operator from a 1940s film: "Westminster double four, double two.”

"They will be successful," Pat declared, "Everyone will want one. They'll get smaller and lighter. Everyone will forget how to dial a number because there won't be any 'dials'."

He knew, of course, only too well how technology works. How it sweeps a young man up, carries him through life, then dumps him high and dry - well, perhaps not so dry.

"When colour film arrived," he recalled, "Pathé asked me to go and re-film their newsreel intro sequence. You won't remember it, Kevin, you're too young. It was a cockerel crowing. Of course, the original cockerel was long dead, so I traced a farmer in Sussex who had a big good-looking cockerel that would crow on demand."

I could imagine Pat motoring down to Sussex from Primrose Hill, probably in some nice two-seater roadster: an Ace or an Austin-Healey, string-backed driving gloves on the leather-bound wheel and Eyemo camera on the passenger seat. (The Eyemo was a newsreel stalwart, serving throughout WWII and the Vietnam War. In 1960, Hitchcock shot Psycho on the Eyemo.)

"I got to the farm and set up all the camera gear," Pat goes on, "Then we put the cockerel on a gate in front of us. Nothing. Absolutely nothing. We poked it. Nothing. I offered it a sandwich. Nothing. Eventually I complained to the farmer, "You said this cockerel would crow.""

Pat laughed at the memory. "The farmer says, 'Well, he likes a drink. If you get a bottle of vodka, he'll like that.'"

So Pat whizzed off to the nearest town and located a bottle of vodka. Back at the farm gate, he filled three glasses with the essential nectar: one for the farmer, one for himself, and one for the cockerel. A few determined pecks at the beverage resulted in a frenzied five-minute cacophony of singing. "The Sinatra of the chicken world." But then things came to a sudden halt. "He fell off the gate fast asleep." Pat, however, had got his shot.

"It wasn't colour that finished Pathé," Pat pointed out, "It was television. No one needed to sit through footage of the Duke of Edinburgh touring Asia in a pith helmet. They got all that on the BBC."

Pathé newsreel closed down in 1970 and Pat's career had come to a halt by the end of that decade.

We started on the dessert, probably a creme caramel or tinned fruit with ice cream.

Pat was thinking about technology and how it moves on. "Black and white film had something that colour can never capture."

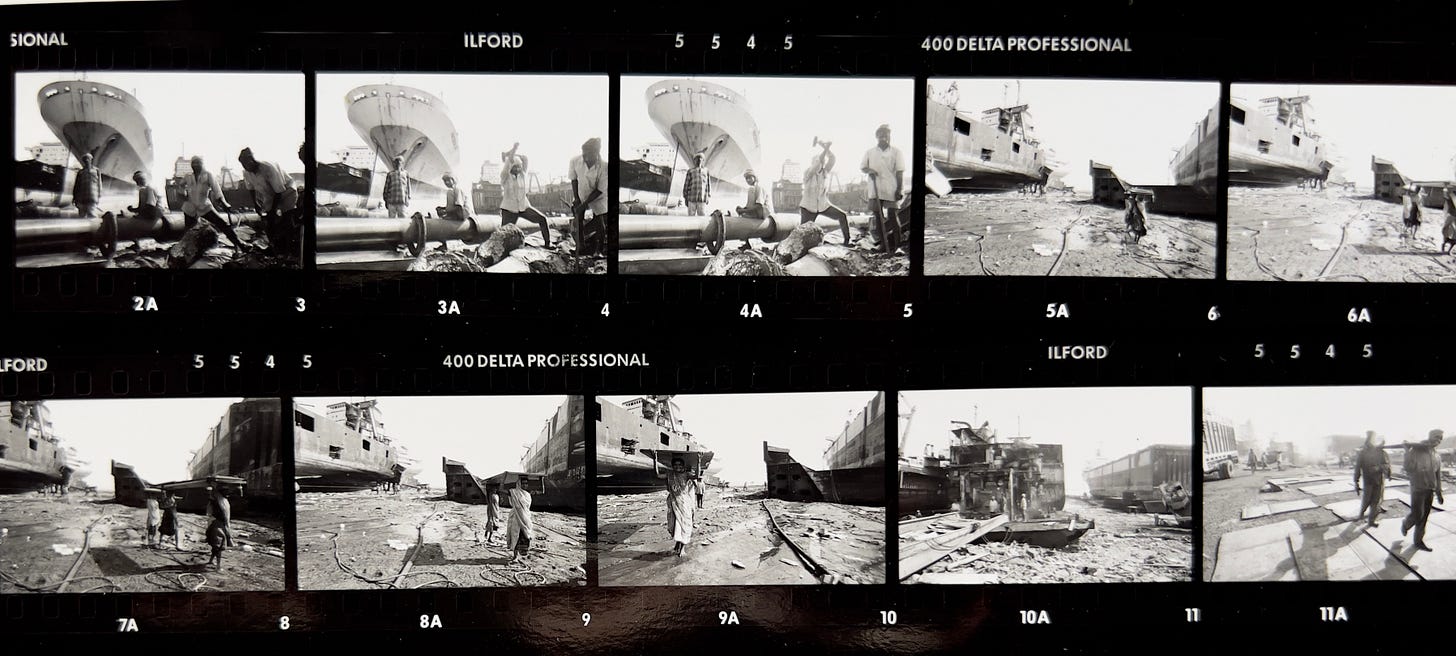

I agreed. "I used to develop my own black-and-white prints." Out came my story. In the 80s, I'd taken a photo-enlarger out to Yemen and installed it in a room in the Old City of Sana'a, spending hours running up prints. The enlarger was like a reverse camera: you projected light through a photo negative, then focused the image on some light-sensitive paper. From there you slipped the paper into a tray of developing liquid and, under a dim red light, watched the magic happen: an image slowly emerging, like a figure from the mist. A good enlarger was as vital as a good camera.

"Have you still got it?" Pat asked.

I shook my head. "After the war in 1994, it was too heavy to bring back. I left it behind... haven't done a print since then."

Pat nodded. “I might have something that will interest you.”

Getting up, he shuffled to the stairs, beckoning me to follow. The house was actually mostly facade. It was one room deep, the stairs narrow. We went up to Pat and Carolyn's bedroom, an extremely old-fashioned spot with an aged bed, a few dusty oil paintings and an immense wardrobe, one of those ancient leviathans with neo-classical columns and pediments. Pat flung open the doors and inside, alongside a collection of blazers and coats, was a complete photographic darkroom.

"Look at it," said Pat. "Look closely."

The first thing I noticed was the wiring: woven brown insulation with bakelite plugs. Then I inspected the enlarger. It was a Leitz Focomat, arguably the best ever built, one of those design classics that gets left behind when technology moves on. Something caught my eye. On the base board was a metal plate and the writing was in German, and with an old gothic script. Pat was chuckling to himself.

"I was 18 years old," he said. "War films unit. 1945. We blasted across Germany with Allied forces, trying to get to Berlin before the Russians. When the Germans surrendered, we just kept going, driving our jeep into Berlin. When we got there, it was swarming with Russians but I went straight to Gestapo HQ on Prinz Albrecht Strasse and took all the photo equipment I could find, including that Leitz Focomat, right from under the noses of the Russians."

He leaned inside the wardrobe and lifted the enlarger out. "Take it. I'll never use it again."

I still have that beautiful piece of kit, sadly unused these days.

Years later, I came across a mention of Pat in a history of Pathé newsreel. 'Howard Thomas recalled that when he was restructuring the Pathe News after 1945, he went to Berlin to do some filming for the War Office, who provided him with an army film unit. Thomas had problems filming in the Russian sector, and ‘liked the way soldier-cameraman Pat Whittaker [sic] faced up to the Russians.' Whitaker was thus invited to join the Pathe News, and he took the offer.'

Thomas went on to become chairman of ITN. Pat stayed behind the camera. When Pat died, Carolyn had him buried in his swimming trunks with a screwdriver in his hand. "He always liked lounging around pools. On the other hand if he's not dead, he can get himself out." The funeral music was certainly not funereal. It included the Burl Ives song "Ugly Bug Ball" which comes from the 1963 movie, Summer Magic. In the film a family who fall on hard times find happiness in a lovely yellow-painted house.

By 2015 Carolyn was gone too. It's a consolation, however, to know that I can always watch Paddington 2 and see their place again.

Your stories are wonderful. I love seeing a new post in my inbox. Honestly the best stuff I've ever read.

Hi Kevin, what a wonderful story. As I read what many would perceive as a mundane note about eggs, I was reminded of a different world:

Until the early 1970s, it was common for Irish farming families to rear a few turkeys for the Christmas market. The farmers used to kill the turkeys themselves and the farmer's wives cleaned them.

Most had a sibling somewhere in Britain. The farmers wives used to sew a hessian sack around a turkey, write the name and address of the sibling in Britain onto the sack, and take it to the post office. That unrefrigerated parcel of fresh turkey was transported to Dublin to catch the night mailboat to Holyhead where it was sorted on a mail train and, more often than not, delivered to the recipient that day. Total time in transit was 24 hours, although to some more remote spots it might take 36 hours.