Saturday 29 April: The British public are invited to swear an oath of allegiance to King Charles III: 'I swear that I will pay true allegiance to Your Majesty, and to your heirs and successors according to law. So help me God.'

October 2022: The [coronation] oath...reflects a period of history that is now over. University College London Political Science department

1898 Daily Mail: People talk of the Sudan as the East; it is not the East. The East has age and colour; the Sudan has no colour and no age - just a monotone of squalid barbarism...and yet there never was an Englishman who had been there, but was ready and eager to go again.

My mother is moving house. She asks me to clear out a wardrobe that's full of my old forgotten possessions. I find stacks of shoeboxes filled with photographs; there's an ex-Army kit bag stuffed with all kinds of things: a camel muzzle, a traditional Yemeni dress, a houkah pipe, and some album covers - no sign of the actual vinyl - filled with ticket stubs. The Clash, The Jam, The Buzzcocks and so on through the roll-call of punk royalty. Somehow it seems like a worthy task for a coronation weekend to go through all this back catalogue. Who was that young man in the photographs? He looks vaguely familiar. My diary from 1979 reveals just how busy student life could be: a one-month-long, incessant round of gigs, cinema, pubs and clubs, pauses for just one night under which I have written, 'Stayed in. Boring.'

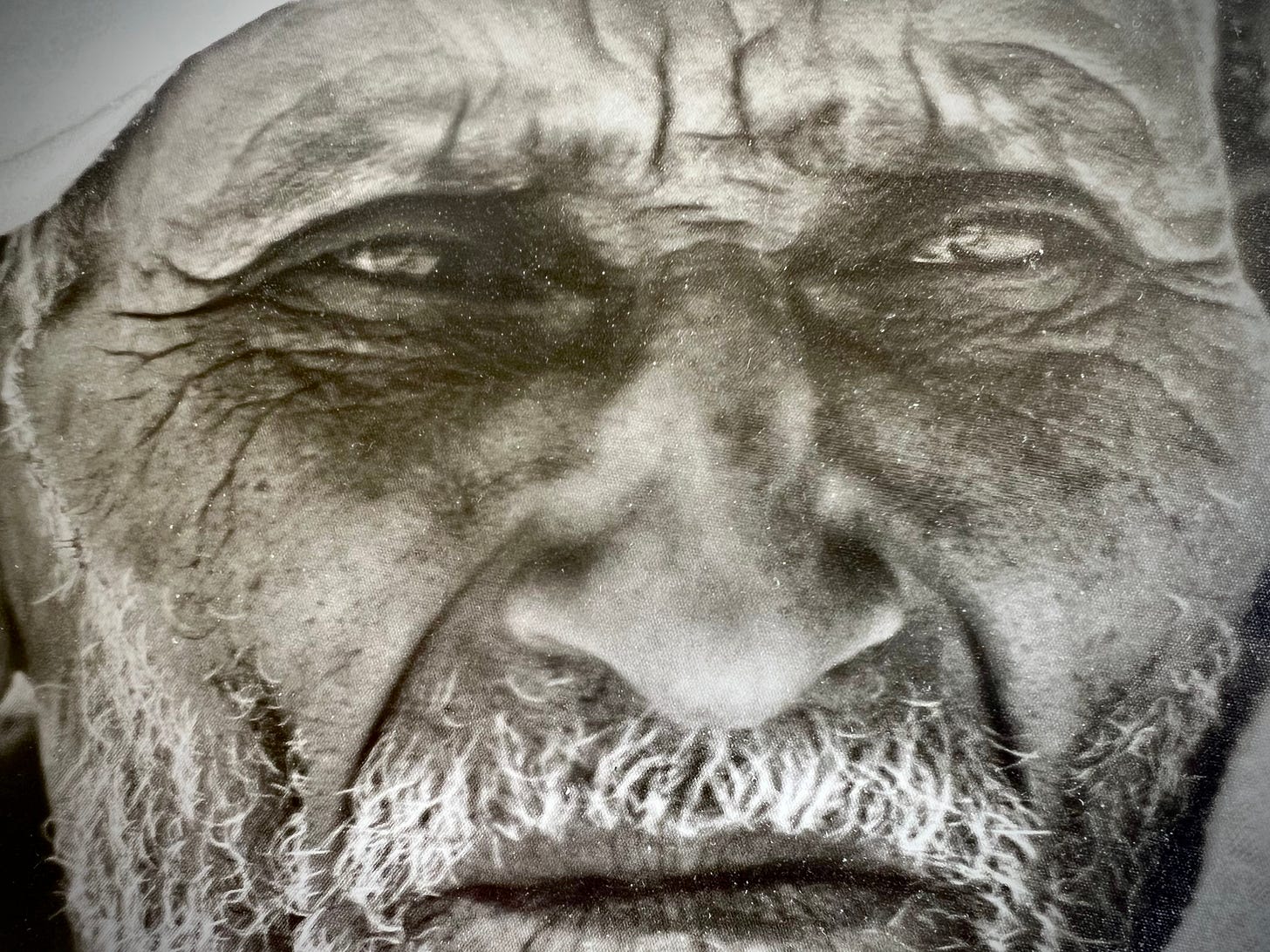

I start a quick trawl through the photos. They are all slides, a format as unfamiliar to anyone under the age of 40 as the Fax machine, Gestetners and Super 8 cassettes. My enthusiasm quickly wanes. I start chucking them on the floor, retaining only those that hold any interest. The problem is easy to see. I was young and interested in escaping modern life. I took pictures of panoramas and wildlife, usually quite badly and always with a wish that I had a better lens. More than that, however, I liked ruins and people in tribal costumes. I avoided anything contemporary. I framed the world, as much as I could, without any reminder of modern contrivances like telegraph poles, cars and roads. Like the men (and I'm sure they are men) who contrived King Charles III's coronation ceremony, I stuck my head in the sands of time and refused to look up.

What I did have in those days was obsessive desire to find parts of the planet unsullied by television and aeroplanes, to discover people and ways of life untouched by modernity. You could still find them in those days, but you had to go a long way, and leave the roads and electricity wires behind. It was that unconscious desire that made me say, 'Yes' when Khalid suggested we go and search for his nomadic family, travelling by bicycle across Sudan’s South Kordofan province in the dry season of 1983.

[for the first part see last week's newsletter]

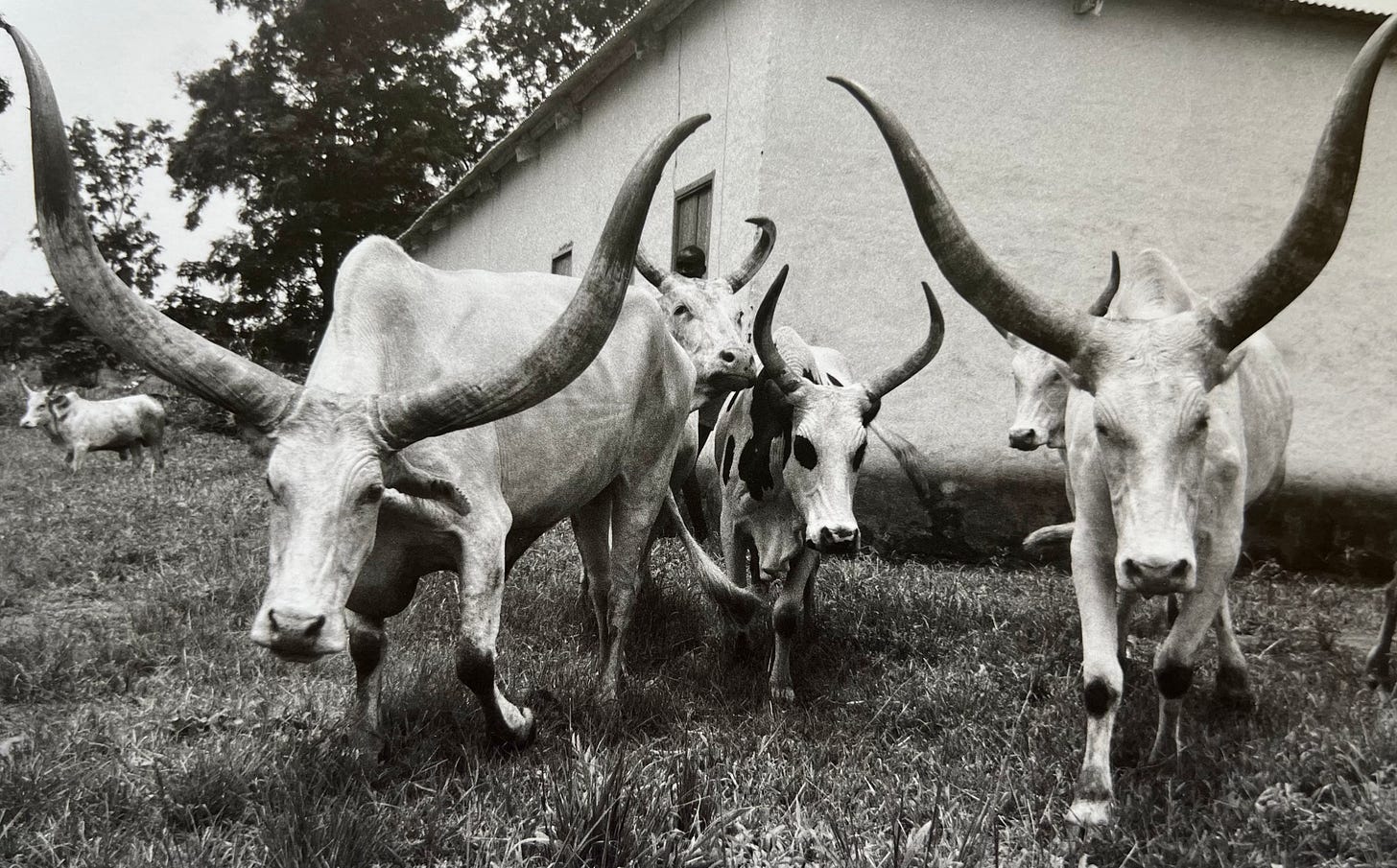

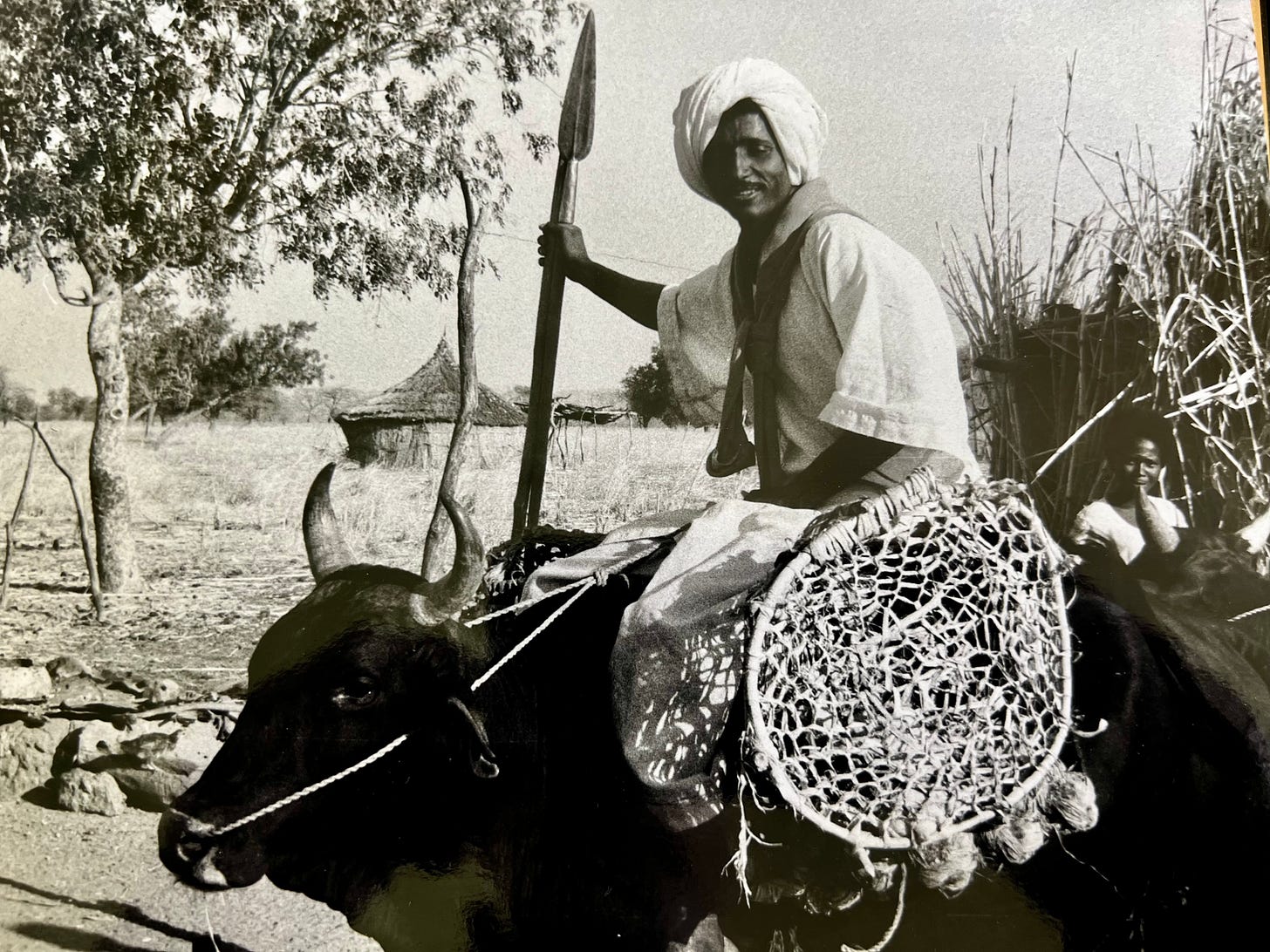

We reached the camp towards evening, when the animals were coming back home raising clouds of golden dust, herded by spear-wielding men riding docile bulls. Everyone was delighted to see Khalid and his new-found friend, the Britaani, Britisher. Each greeting was long and elaborate, involving multiple handshakes and a repetitive call-and-response that seemed musical.

The huts were as simple as pop-up tents - domes of woven grass, patched in places with bits of leather, they sat directly on the ground. Inside were a few possessions, hardly recognisable as such to a Westerner like me: everything so battered, weathered and worn, covered in dust. A scrawny chicken was chased around by the small children until it was caught and slaughtered. The family were celebrating. Later, we all squatted down around a metal tray and tucked in. The chicken was as tender and sweet as an old pair of boots.

I slept on a grass mat, waking before dawn to the cockerel and the sounds of cattle moving out. Breakfast was a glass of sugar syrup with a little tea. We rode the bulls out to the waterhole and watched the women and children filling up their leather water bags. I was a bit annoyed that the waterhole itself was a concrete hand pump installed by Unicef; I would have preferred something traditional for the photos. Khalid laughed at the idea. "Before this we had to dig out the well every time we arrived. Very hard work."

Next day we cycled to Lake Kailak. This waterland, billed as a paradise by Khalid, was underwhelming. The shore had retreated a long way, leaving a craquelure of mud flats dotted with abandoned reed canoes. When we eventually found some Dinka fishermen they were washing in the shallows. They were happy to sell me a set of fish spears. "No fish here."

Kailak, like its neighbours, Kundi and Abiad, was shrinking, evaporating into the blue skies, never to be replenished. If only the retreating waters had revealed a line that read, "Beyond this point, there be devils", but they did not. Everyone hung on, hoping for rain. And in that edgy fractious waiting, there was opportunity to find fault with your neighbours. The Dinka were friendly with me, but less so with Khalid who had changed out of his teacher clothes and into the white tunic of traditional Baggara tribal dress. These young warriors were stark naked, burned to the black of a crow's wing, almost bluish, their faces and bodies scarred with tribal patterns and their heads shaved. They were searching the mud at the water's edge for thick white grubs which they hooked out and ate. I tried one. My face made them double up with laughter and clap their hands in delight. Then they ran their fingers through my hair, "You use cow urine to get this colour?"

"It's natural. It grows that way."

"Really?"

Khalid and I returned to his family camp. The culture gap between the Arab and African seemed enormous, but they were both cattle-herders, driven by the needs of the animals on which they relied totally. In that vast landscape the potential for conflict seemed so remote. There was so much space. When Khalid and I left, on our bicycles, the old men bearing spears, came along for a while, riding their bulls like a guard of honour, everyone laughing and joking. The only man on a horse was the chief. It seemed to me that I was right to revere that ancient way of life over its lacklustre modern alternative.

Sitting at my kitchen table, forty years later, I am working my way through those shoe boxes when I spot an envelope with Sudanese stamps. It seems to have never been opened. I pull out a single sheet of green notepaper. It is a letter from Khalid, sent to my mother's address in England in 1984. Had I ever even seen it? I don't remember it at all. "Thank you for the photographs," he writes, "The people will be very happy in seeing them."

But all is not well. "About the draught in the Sudan, it is severe and tense in Kordofan, most of the farmers and nomads immigrated their homes, and inhabited near Khartoum, but by now they have been taken to Kordofan once again with the promise to be given support (food) for a year."

I tuck the green paper back into the envelope.

At some point in that same year, the government of Sudan did send the Baggara tribe back to Kordofan, but not only with food. They gave them guns to replace those old broad-headed spears. They were encouraged to raid the tribes to the south. Large numbers of Dinka women and children are said to have been captured and sold as slaves.

In the years that followed some of these guns and fighters slowly drifted westwards into Darfur and coalesced into a force that became known, to the terrified African villagers, as the Janjaweed. The name is thought to be a corruption of two Arabic words: jinn, meaning devil, and ajawid, meaning horses. This ragtag army gained strength from Libyan weaponry, but the main focus remained grazing rights until about 2003 when the Sudanese government started to use them as a counter-insurgency force. In the years that followed they murdered an estimated 200-400,000 people and their leaders were indicted as war criminals. Around this time the son of a Baggara chieftain, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo aka 'Hermetti', joined the Janjaweed. He had completed three years of primary school and some say was a camel thief before running a furniture shop. He rose rapidly and was soon associated with the most brutal acts of violence, rape and genocide against African tribes. Witnesses placed him at the site of several terrible massacres, overseeing burnings, torture, rape and murder.

In 2013 the Janjaweed, led by Hermetti, was renamed the Rapid Support Force and became the powerbase for him to become deputy head of the Transitional Military Council in 2019. His men took over gold mines in Darfur and he is now extremely wealthy. Once in power he quickly forged links with autocratic violent men, including Mohammed bin Salman in Saudi Arabia, and Vladimir Putin. On April 16, 2023, the RSF launched a takeover bid against the regular Sudanese Army. Hermetti, it seems, wants to be king.

But I don't want to leave you with that vile history of one man's ruthless rise to power. Having tucked Khalid's letter back in its envelope, I notice the postage stamps. They are for the 1984 Olympics which were held in Los Angeles. Sudan sent seven male athletes. They won no medals. The country had never won a medal since first sending competitors to Rome in 1960.

From 1984 onwards, of course, the country was gripped by drought, famine and communal violence, reaching a peak of horror in the years immediately before the 2008 Olympics. Surporisingly the 800 metres competition in Beijing had two Sudanese competitors: Abubaker Kaki Khamis was from the Messeria Baggara tribe, the same group as my friend Khalid, and the same group whose menfolk - a few at least - had joined the Janjaweed. He had been fêted by the president, Omar al-Bashir, presented with land and had songs composed about his prowess.

The other athlete, Ismail Ahmed Ismail, was from the Fur people, an African tribe who gave their name to the province of Darfur, 'Home of the Fur'. Of all the tribes in the province, the Fur had suffered most at the hands of the Janjaweed. In that Olympic final, Ismail began badly, hanging on to last place then managing to box himself in. When the eight runners came around the final bend, however, he got himself behind the eventual winner, Wilfred Bungei of Kenya, and held on to get the silver, only losing by 5/100ths of a second. After almost half a century, the Sudan's first Olympic medal had gone to one of its marginalised and oppressed communities.

Brilliant storytelling and I love the premise - of connecting present day stories to your past travels

Brilliant!

Did you ever find out the reason Khalid did not want you eating from the Hammar people?