How is it that human groups frequently divide into two competing factions, neither of which ever quite manages to achieve full destruction of the other before the balance tips the other way? Man United v Man City, Inter v AC Milan, Tory v Labour, Republican v Democrat, Us v Them, South v North. Need I go on? There always seems to be a split almost down the middle, with a few dissenting voices that refuse to pay allegiance either way.

AD 40: Roman writer Phaedrus produces several volumes of fables including one about two bald men fighting over a comb.

AD 501: After a disputed chariot race In Constantinople’s hippodrome, the ‘Green’ team supporters ambush the ‘Blue’ and kill about 3,000 of them. The two rivals dominate what is Byzantium’s most popular entertainment and some historians claim they evolve to become political factions. No historian, however, can discern any policies or objectives for either clan beyond the defeat of the other.

AD 532: Tax demands from the Byzantine emperor, Justinian, manage to unite the Blues and Greens and unleash a riot in which much of the city is destroyed. The emperor is about to flee when his wife, the formidable Theodora, insists that he stay and take action. Loyal troops from outside are sent in and massacre 30,000 before peace is restored. The net result for Blues and Greens is that chariot races are not run for several years and never regain their magical power. That one moment of unity for the two clans has destroyed the thing they love and the reason they exist.

November 2022: Climate talks to save the planet from catastrophic meltdown get bogged down in ‘Loss and Damage’ disputes over the financial compensation due to the global south for the historic damage done by the north.

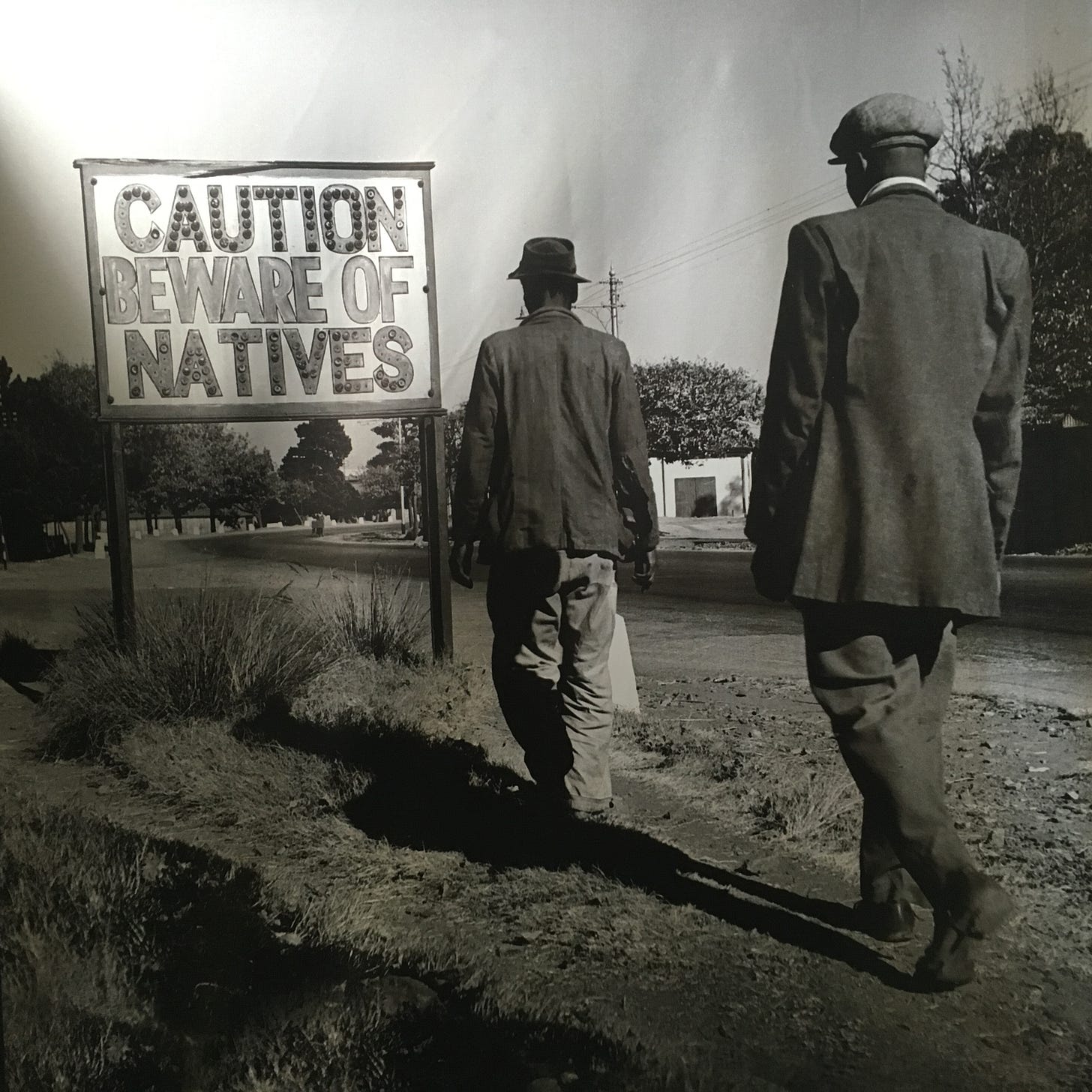

March 2016: I travel to South Africa and set out from Durban on a long journey into the highlands. Everywhere I go, I hear historical tales of conflict and killing. The bodies pile up.

Standing at the gate to Three Trees lodge, I look across the valley to Spion Kop. It is a dusty nondescript hill, thinly wooded. The walk across is not strenuous and I go slowly, watching for animals and birds, particularly the long-tailed widowbird which looks like a flying black dishcloth. There are supposed to be white rhino too, but I don’t see them. The morning is peaceful and I’ve had an excellent breakfast. The lodge is built in a reassuring and familiar colonial style: well-made furniture on spacious cool verandahs, the walls dotted with botanical prints, the colours all muted and natural with plenty of polished hardwood and brass. Everyone is friendly and cheerful.

You might suppose that The Battle of Spion Kop during the Second Boer War (1899-1902) was just another bloody skirmish in the annals of imperial history, but the ripples it created are fascinating. The British were moving up from the coast, trying to raise the siege of Ladysmith 25 miles away, and had decided that capture of the hill, lightly defended by Boer soldiers, was essential to that goal. One misty night in January 1900, around a thousand British soldiers climbed the slopes and easily chased the defenders away. A few of the soldiers had brought spades and they now dug shallow trenches, not realising they were digging their own graves. As dawn came up, the thick mist lifted and the British suddenly realised, with horror, that they had only captured a secondary summit of the main hill. The Boers could now fire on them and they did, following up with a frontal assault and some brutal hand-to-hand combat that killed 243 British soldiers and 68 Boers. In the end the British prevailed, but were so shattered by the experience that they withdrew.

The top of the hill is bare and shadeless. I’m glad to have carried a water bottle with me, something I usually manage to forget. The sole distinguishing feature is a long raised rectangle edged with white stones, like a municipal flower bed, except there are no flowers. This was the trench that became the grave.

Among the British in 1900 was a young journalist called Winston Churchill. Among the stretcher-bearers was a young Indian called Mohandas Gandhi. And among the Boers was a young general called Louis Botha who later became first president of The Union of South Africa. One of the British wounded was Lionel Charlton who survived the experience, later joining the nascent RAF during WWI. It’s said he was the first man to drop a bomb from a plane, but if that is true, he soon realised his mistake. In the 1920s he witnessed the effects of the first carpet-bombing campaign, a strategy begun by the RAF in Iraq. As a result, he resigned in disgust. (The RAF did not stop, however. In 1996, in a remote wadi north of the Yemeni city of Aden, I met an old man whose village had also been bombed by the British in the 1920s.) The men who died at Spion Kop were from all quarters of England and the word ‘kop’ somehow transferred to the steep-sided football terraces of various stadiums, most famously Liverpool, but also at both Sheffield United’s Bramhall Lane stadium and Hillsborough, home to their great rivals Sheffield Wednesday.

Driving on through South Africa, I get to Blood River where there are two museums connected by a gated bridge across the river. The gate is locked. The two museums do not talk to each other. In one there is a huge ‘sculpture’ of several life-sized ox carts that the Dutch Voortrekkers had brought to the banks of the river in 1838 when they were attacked by the Zulu army. Thousands of Zulus died at a cost of three wounded Voortrekkers.

The museum is stuffed with souvenirs of those supposed heroic trekker days and has a shop. The other museum is for the Zulus. They don’t have a lot to show, or sell. One of the custodians asks me, “What did they say to you at the other museum?”

We talk about apartheid. He tells me that one of the tests for ‘blackness’ was to see if a comb would stick in your hair. Some of his relatives had African hair and were consigned to being Black; others did not and were granted Coloured status. I feel sorry for their museum. It doesn’t have much to show and there are no other visitors.

The tourist resorts here are all similar, offering decent food and cold beer inside a style that deliberately harks back to colonial days. Zebra skin rugs, sturdy hardwood furniture and mosquito nets stroked by quiet fans. The views are always superb, revealing an Africa that is filled only with trees, mountains, rocks, animals and birds. No people are visible unless dressed in khaki uniforms. The people who bring your drinks are black. The people who tell you about the place are white, apart from questions relating to wildlife. Everyone is relentlessly cheerful. There is often a charitable social programme and tourists can visit a school and see children in uniforms line up and sing something. The schools are familiar for me. I spent years working in such places.

I can’t fault these lodges, but slowly my mood shifts. The workers don’t eat this food. They live in very different houses. It feels like there are two camps and, without being consulted, I am automatically enrolled as a member of one, the privileged one. It makes me uneasy. I don’t want to be waited on.

I once went for a year in black Africa without seeing another white face and after a few weeks I forgot there was a difference. My friends forgot too. We all forgot that the accidental colour of our exteriors was important. It was bliss to have that easy equality. We ate the same food, drank the same dirty water and caught the same diseases for which there was no medicine for anyone. Then, when war intervened and I needed to get out, I got out. I could do that because I happened to be white. The bush pilot wouldn’t have accepted any of my friends. In that moment I connived with the normal world and rejoined it.

The KwaZulu Natal battlefield tours have become a great money-spinning bestseller, but I feel that something is missing, some part of the story. I stay at Hilldrop which was once the home of Henry Rider Haggard, author of King Solomon’s Mines. I’m relieved to find that the arch-storyteller of imperialism was uncomfortable with what he found in the Southern Africa after the Zulu War of 1879. He notes that 100 whites occupy 600,000 acres while 16,000 ‘natives’ have half that. ‘Surely these figures are disproportionate to the relative needs of the races.’ He tours the battlefield sites too. At Ulundi he picks up fallen bullets from Martini Henry rifles and hears the complaints of an old Zulu fighter. The British lost 13 men in the battle, he says, but slaughtered 1500 whose bones were piled into wagons and taken away as manure. (In Durban there was an outcry against this and the bones were eventually buried.)

I meet Lindizwe Dalton Ngobose, great great grandson of chief Sihayo of the Zulus. Back in 1879 the British used a murder among Sihayo’s family to justify their invasion of Zululand. Dalton takes me around the site of Rorke’s Drift, once a mission station defended by 150 British against 4,000 Zulus. Most of the British soldiers who fought a desperate defensive action here are remembered by name, 11 of them won the Victoria Cross. The Zulus who died were not counted.

Then we go to Isandlwana, scene of one of the British Army’s greatest defeats when 1,800 men were overwhelmed by Zulu warriors. It was a rare occasion when old-fashioned hand weaponry defeated modern firearms, but it was a victory for which the Zulus would pay dearly. The hill where it happened is dotted with red boulders, aloe trees and white-washed cairns, supposedly where the dead are buried though I cannot imagine the hyenas respected that.

We sit on a red boulder in the shade of a tree and Dalton rebalances me a little. He tells the tales from both sides with equal authority. A hundred yards away down the hill, in the shade of another tree, is a group of white tourists with a white guide. They are all dressed in the standard uniform of the safari with khaki sunhats. They all look a bit freckled, like me. At some point in the tale of the victory/debacle, Dalton jumps to his feet and unleashes a bloodcurdling Zulu war cry, “Heybe Usuthu!!”

The huddle of elderly white tourists are visibly startled and huddle closer together.

Leaving this area I travel west towards the coast. Impoverished little shacks appear: tin-roofed with cracked mud walls, stuck at random places in the landscape. Sometimes there is a wire for laundry, a few rocks that someone must sit on. They look unloved. The surrounding landscape is grazed to stony oblivion. The people look as though they are wearing other people’s clothes, all of them too big. There are no tourist resorts.

At Eshowe I head for the George Hotel where I’ve heard that an old friend, Peter Engblom is living. When I enter, I know he is there: the hotel is plastered with his magnificent photographs and I can hear his voice booming from the bar.

Peter is the descendant of Norwegian missionaries who came to proselytize the Zulus and stayed on. Having studied photography in Germany, he became a museum designer, but his true vocation was as a gifted prankster and artistic disrupter. In the late 90s when I first met him in Durban, he was living in an abandoned factory surrounded by ten giant wax vaginas that had been left there by a visiting artist. He was still doing museum work, but only to survive. His real passion had become a Zulu warrior called Mpunzi Shezi who, Peter claimed, had travelled to Japan in the late 19th century and become an expert in tantric sex and Zen Buddhism, also teaching the Japanese about the Zulu philosophy of Ubuntu – roughly translated as ‘kindness’. To prove this claim, he was busily creating old letters, documents and telegrams with all the skill and tenacity of a gifted banknote forger. His plan was to insert them into the stream of human culture via the internet and exhibitions, confounding everyone’s expectations and assumptions about Africa.

Seventeen years later I find Peter still impishly obsessed. We go down the hotel garden to his ‘house’, a tin-roofed cow shed with a few scraps of home-made furniture, including a desk where he is busily forging the documents that will prove Mpunzi had travelled on to India, witnessing the crowning of King George V as emperor in 1911 and learning how to rustle up a pork vindaloo. It is all utterly bonkers, but somehow I feel the only possible sane response to this country and its bloody conflicts

“Ethnic identity is a swindle,” Peter says, “They are cultural constructions that we are tricked into believing. My grandpa was a missionary who cultivated belief, but once people believe they stop thinking. I’m trying to make them think.”

I had lunch with him and left him at the bar, promising to come again in a few years and see where Mpunzi had gone next. But it was not to be. Sadly Peter died at the age of 63 in 2020.

Being a resident of Durban, this post resonated with me. For one, I haven't (yet) visited the various battle sites and museums you talk about. The dichotomy in how people (still) live and are memorialised that you notice is appreciated but bitter to swallow. Heartbreaking that many years later, dignity has not been given to those lives. Thank you for writing this piece.