Friday 5 July A new government is elected in the UK, one that promises honesty and integrity - things that the British electorate have not experienced in politicians for some time. Keir Starmer’s first speech promised that ‘the work of change begins immediately’. Doing that work well, of course, will be difficult - and there’s more than one way to do a job. While there is plenty to be done inside Britain, I hope the fresh approach extends to foreign policy where honesty and integrity have also been sadly lacking.

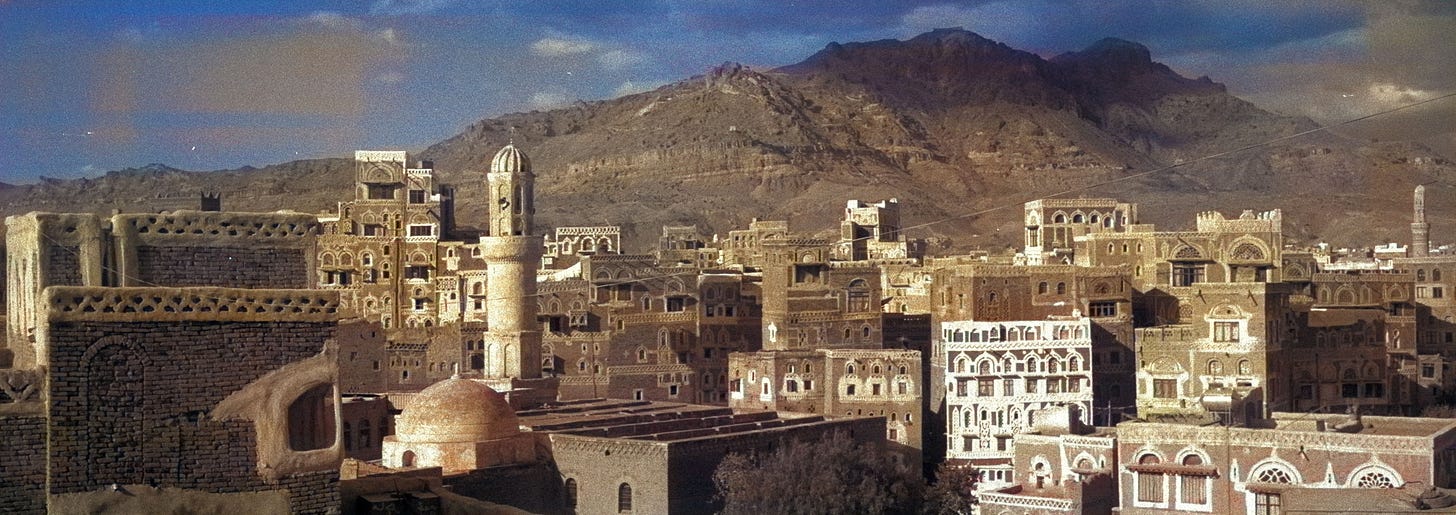

In 1988 I moved house in the Yemeni capital, Sana’a, taking up residence in Beit Qadi, the ‘house of the judge’, in the Bab Shu’ub area of the Old City.

Moving into a tower house in the old city of Sana'a was not quite the same as any other place. First of all the exterior, all eight floors of it, had to have its decorative white bits rejuvenated. Each arched window had its adornment, every floor had a zig-zag relief across it, and all the parapets needed painting with a thick coat of weatherproof white plaster.

There was a hammering on the front door and when I peered down through a hole in the base of a casement window saw three workmen. It's not necessary in a Yemeni tower house to go down and physically pull back the hefty wooden beam that locks the front door. There is a rope that burrows down through various pipes and slots from the upper floors and is tied to that beam. A good haul on this rope pulls the beam back, opening the door without any need to descend.

New arrivals would then climb several short flights of narrow stone steps. On the first floor they would have to negotiate Ummi Sufia, an ancient old lady resident, somehow related to the landlord, who came with the building. She spent her days sucking on a hookah pipe and waiting to interrogate visitors. First she screeched, 'Man?' (Who's that?) down the stairs, then, depending on the person, she might invite you to a 'puff of smoke'. From that level there were many more steps, passing two barely used floors. If the house were one occupied by locals, the visitor would have to make a lot of warning noise, constantly muttering, "There's no god but God', lest you outrage the modesty of a woman, by seeing her unveiled nose and mouth. (Ummi Sufia managed to smoke a pipe without ever letting anyone see either by dextrous use of head coverings.)

In the unlikely event that you did meet a woman on the stairs, she might scuttle past, veiled face averted, as if you were a dangerous plague-carrying danger, or she might engage in conversation: there was no telling. Once, a veiled woman did stop and talk to me and appeared so friendly that I asked her name. At that she screamed and bolted. I never again made the same mistake.

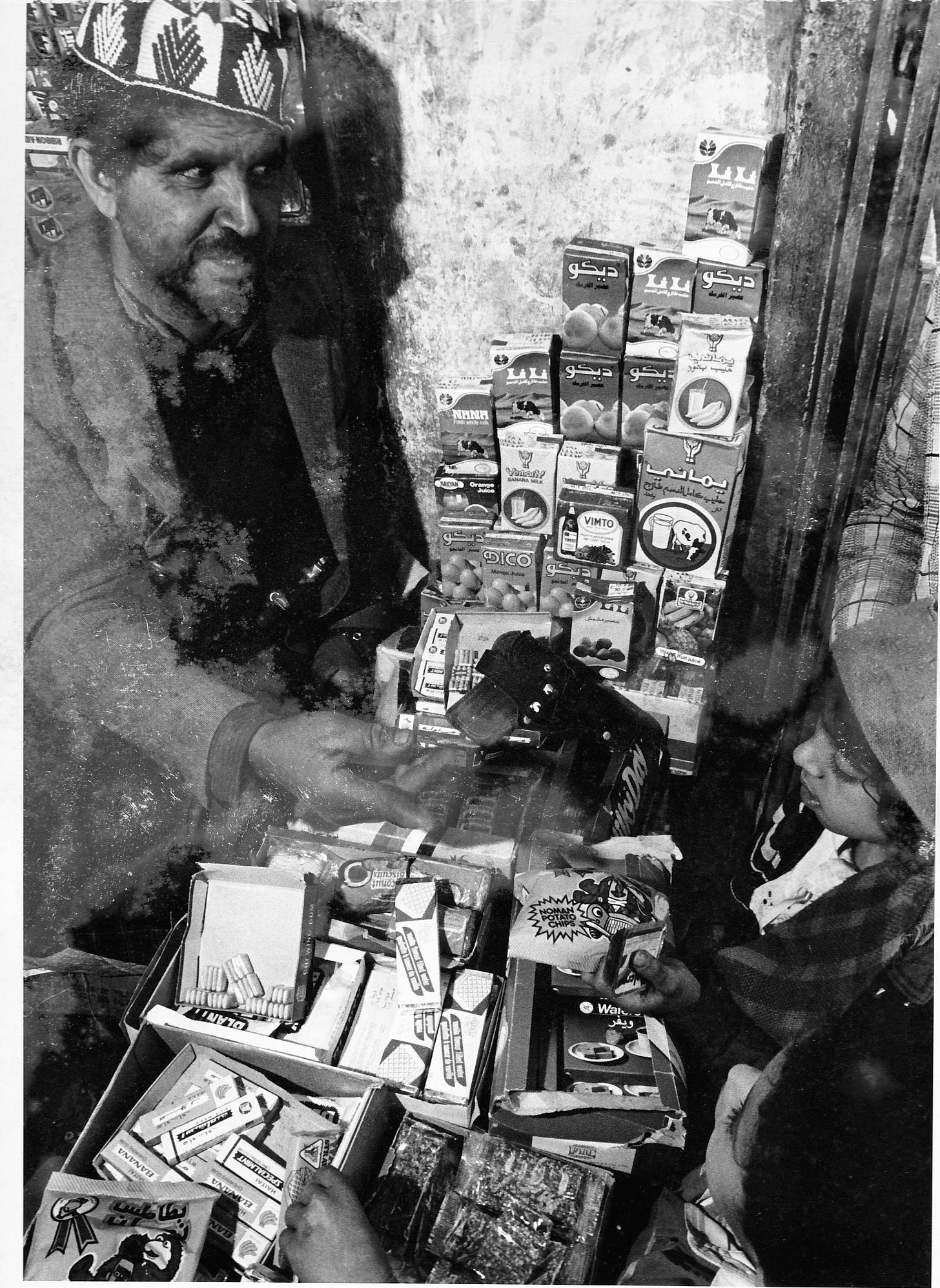

The workmen huffed and puffed and made their polite shouts of warning, then on the top roof they tied some very old hemp ropes to whatever fixed points they could find and lowered a horizontal wooden board where they could sit. Once in position (I cannot recall them climbing down to the board but they must have done), they began. The entire process might be termed slapdash. Vast quantities of paint plastered all over the men, their clothes, the ground below - with quite a small amount actually connecting with the intended target. There was a tiny shop eight floors down under the house, a hole in the wall really, and though Muhammad, the owner, got splashed, he did not appear to care, or even notice.

Despite such apparent casual unconcern, the net effect was beautiful: the neat geometry of pattern cut with a measure of devil-may-care irregularity. I liked that. When I grew up, my dad was working as a building site carpenter. In his youth, however, he had completed seven years as an apprentice furniture-maker. I remember he said that the entire first year was taken up with learning to sharpen tools. The second, I reckon, was occupied by sharpening clichés: "A bad workman blames his tools", "Measure twice, cut once", "More haste, less speed", and most frequently, "If a job's worth doing, it's worth doing well". He built us a house and made the furniture. I can remember watching him knock six-inch nails into roof joists: a tap to set the nail up, then two perfectly timed swings of the hammer to drive the nail down. Perfection was always the objective, a type of perfection based on precision. He could saw in straight lines. I struggled.

The Yemenis, however, seemed to offer as different notion of what perfection might be, these workmen suggested that true perfection had a dash of chaos thrown in.

After a couple of days in the house it became apparent that there was a water leak in the bathroom. That was a double problem. Water is precious in Sana'a, but also I'd started using the bathroom as a photo darkroom to develop black-and-white pics. The constant drip was annoying. I went to the market and found a plumber. There was a place where all types of tradesmen would wait to be engaged, each sitting behind an emblematic set of tools. I chose one and we walked back, him puffing on a cigarette.

In the bathroom I showed him the problem. He lit another fag and puffed contentedly while it remained glued to his lower lip. Then he hit the dripping connection hard with a hefty adjustable spanner. The pipe split and a jet of cold water burst out, hitting him in the chest. Laughing he reached out and pressed a finger on the hole, sending crazy spurts of water in several directions, drenching me and all the bathroom to his immense amusement. With this water constantly blasting all over the place, he cut the two pipe ends, inserted a new fitting and tightened the nuts. The water eased back, then stopped. There was only the sound of drips falling from the roof beams and all surfaces. The pipes were a jumble, nothing exactly horizontal or vertical. Everything skew-whiff, my Dad would have said. The plumber took a drag on his cigarette. I stared in disbelief. It was still alight. Magic.

How did you do that? I asked. He grinned and with a flick of his tongue, the cigarette disappeared inside his mouth, then a second later reappeared. I decided that he had taken plumbing to a new level, a type of performance art. "No job's worth doing," he might have said, "Without panache". When he had gone, I brought back my darkroom kit and started printing pictures again.

Welcome back! Feels like you’ve not missed a beat.