1988 The remnants of Colonel Gaddafi's failed pan-Arab Alliance take refuge in northern Darfur after defeat by combined French and Chadian forces. Their weaponry reportedly falls into the hands of the local Rizeigat clan. These people are part of a larger tribal federation called the Baggara, semi-nomadic camel and cattle-herders who regard themselves as 'Arabs'. They begin to use the weapons in disputes over grazing rights, disputes that are escalating as desertification intensifies. Their enemy, all too often, are people and tribes that they identify as 'African'.

2003 Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo, 'Hemetti' emerges as a leader of the Janjaweed, a paramilitary force that commits atrocities against ‘non-Arab’ populations in Darfur. He is the son of a Rizeigat tribal leader and, in some accounts, part of a group that were driven by drought from their lands in northern Chad.

2014 Unable to control the Janjaweed, the Sudanese government absorbs and renames it as the Rapid Support Force (RSF). Hemetti, now a general, oversees 'Operation Decisive Summer' in which his men are supposedly fighting rebel factions, but in fact use the opportunity to burn, loot, rape and murder their way through defenceless villages in South Darfur. Several eye-witnesses report Hemetti's presence during the worst atrocities against unarmed civilians.

March 2023 Sheikh Mansour, owner of Manchester City football club and vice-president of UAE, is photographed alongside UAE president, Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed, smiling as he meets Hemetti, the Sudanese warlord who has now embarked on a round of international visits apparently designed to establish him as a statesman.

September 2024 In the Sudan civil war the RSF appear to be gaining ground as a result of new deliveries of weapons. A Human Rights Watch report reveals that the RSF have been using 120 mm thermobaric shells, a particularly nasty piece of military hardware that deliver powerful shock waves, rupturing the lungs, eardrums and eyes of anyone nearby. Those at the centre of the explosion are obliterated, those nearby can suffer fatal burns and internal injuries. Photographs found on social media reveal that the RSF arms were manufactured in Serbia in 2020, then sold to the UAE Army. Despite this damning evidence, the UAE denies supplying the RSF. Other sophisticated weaponry has also been seen: Israeli multiple rocket launchers, Chinese drones and Russian anti-tank missiles.

I search the attic first, crawling with headtorch around the boxes filled with books and paperwork from long-forgotten projects. There are all sorts of distractions: my fossil collection spills out and has to be tidied up, there is a ticket stub from a 1976 rugby match between England and Wales, a match that I then find on YouTube, and there is the periscope from a burned-out Russian tank that I came across in Afghanistan. But these are not things I set out to find: I've been thinking about the time I saw the shadow puppet theatres of Indonesia and somewhere, I'm certain, I've got one of those puppets.

I know this is all avoidance behaviour. I know there are more vital issues. Palestine and Lebanon are what is in the news. But somehow I can't begin. The current situation is too terrible. As for Sudan, it is not in the news, but what is happening is also horrible.

What I want to find is a puppet: one of those spidery simulacrums of humans made from leather and wire coat hangers. In the hands of a puppet master, they come alive. I want to remember that human beings do create good things.

The puppets, however, remain elusive. Instead there's a shoebox filled with cassette tapes - my rummaging hand picks one out at random. "Anjouan. 13/9/99..." That starts a long digression to find an actual cassette tape player that still works, then listening to some drumming and singing from the Comoros Islands. Hours have passed. Then I go into a space above the stairs where, for many years, we have shoved unwanted posters, bags and framed pictures. The dust is intense. At the back I discover two knobkerries, those heavy-ended fighting sticks. One is black and more like a walking stick. I’m not sure where that came from. The other is much shorter and beautifully polished. I weigh it in my hand. I remember the Masai warrior who sold it to me, warning of its power.

"If a man does rob you, and he is running away, then you must throw this after him. It will chase and catch him!" He made it sound like the stick was alive and wanted revenge for a crime yet to come. He wheezed with sinister laughter. "It can break both legs. For certain, that man will not be robbing you again!"

For such a dangerous weapon, it appears remarkably unthreatening. There are no metal parts nor anything sharp. It is the sort of weapon that can be carried without raising suspicions. It is, after all, just a stick.

When I was in Sudan in the 1980s, I collected weapons. I only had to see a man with a traditional spear, or a fancy scabbard and knife, to move in and ask for a closer look. If you had asked me where that fascination came from, I would not have known, but I might have summoned up some waffle about them being 'historical artefacts', or perhaps that they were 'beautifully made'. If you had persisted, I would have explained that, as a boy of firmly pacifist parents, I had never been allowed any toy resembling a weapon. Even a dead stick, cunningly adapted to fire a barrage of imaginary bullets, could be confiscated. Those childhood restrictions had triggered an enduring interest, although to be fair, I think they also established an enduring dislike of violence too.

In El Fasher during the early 1980s I bought knives with crocodile skin sheaths from the Zaghawa tribe; in Kadugli I swapped a Swiss Army knife for a Nuer spear collection, and from others came home-made machetes and ceremonial 'money' spears, hunting bows, sheaths of arrows with deadly barbs, and a wickedly hooked knife that, I was told, was designed to cut human throats. What I did not see was firearms. Soldiers were not much in evidence either. Guns were a rarity.

My trips across the country often resulted in memorable encounters. In 1984 I was on a market truck travelling out from Nyala in South Darfur towards South Kordofan province. This was a peaceful area, sparsely populated. Occasionally you might glimpse a clutch of mud and thatch huts, often positioned next to a tall outcrop of smooth reddish rocks, a place where water might gather. Sometimes there would be a tin shack next to the road and we would stop to unload a few items, usually a sack of red onions and a battered cardboard box of soap. There would be a clutch of people waiting to get on - there always seemed to be more getting on than off. There was, of course, no indication of the racist horrors that were to be unleashed in this area by the RSF three decades later.

These trucks travelled between isolated markets and were always overloaded. Breakdowns were frequent, and sometimes serious. This time, as we wallowed through a dry river bed at night, the axle snapped.

We slept by the broken truck and the following morning I decided to take a chance and walk to the next village. Perhaps there would be another truck. When I arrived, however, the village was only able to provide shade under some ragged pieces of sackcloth and a glass of sweet red tea. No truck.

I spent a night there, sleeping on a wooden bench. In the morning I walked around, admiring a herd of white cattle in a thorn brush enclosure. These people were from the Baggara tribe who I had come across on a previous trip and always found to be very friendly. They invited me to eat, a thick porridge and sauce eaten from a communal bowl, and told me there was another camp nearby, a different tribe who they assured me, 'had come from Nigeria'.

Next day, intrigued and disbelieving, I set off to find this mysterious group.

I walked for a mile or two through the flat dusty savannah. Every now and again a hornbill would swoop away from the top of an acacia tree, otherwise nothing moved. Then I saw the cattle, and their herders. These people were different: tall graceful youths, their arms draped over a long stick across their shoulders. In the drab subdued world, their dark robes were emblazoned with colourful designs of stars and zigzag patterns. They were smiling too, pleased to have some diversion from the boredom of herding. In those toothy smiles were quite a few home-made gold teeth.

Our conversation was limited. These people spoke a language I did not understand at all. I examined their faces: sharp featured and intelligent with some facial tattoos and kohl-rimmed eyes, very different to the broader Baggara visages from earlier that day. One of the youths, I noticed, had a tiny mirror no bigger than a mosaic tile, that he was using to check his appearance. It was woven into a long side lock of hair. They were very concerned with looks, not least their own, but it was their sticks that I admired. They were black and weighted at one end. Without much discussion, I bought one.

The camp when I reached it was a simple collection of temporary shelters, no more than cloths thrown over a low wooden frame. Under these the women were squatting, chattering loudly. My appearance caused a stir: lots of arm waving with a clatter of metal bangles. It wasn't clear if this commotion was friendly or not. An older man came over who spoke a little English.

"We are coming a long way," he told me. "With our cattles. We are Fulani."

One of the young men began singing in a strange high-pitched voice. I asked what the song was about, a question that brought on much head-shaking and apologies for poor English.

"It is something."

"Okay." The song was quite long. "Anything else?"

"It is about beautiful hair."

He made a comment to the singer and they all started laughing. The youth checked his hair in the tiny mirror. I didn't get any more information.

Forty years later, in the loft, I am still searching for those shadow puppets, rummaging in the corner where the dust is thickest. Then my hand touches a rolled-up newspaper. I pull it out. It is a copy of The Guardian from Wednesday 14 November 1984, the year George Orwell chose as his setting for a dystopian nightmare. My immediate thought is that it might hold that Fulani stick, that fighting stick that had crossed Africa from West to East and, no doubt, smacked many a cow on the way. Or perhaps it will be one of those shadow puppets.

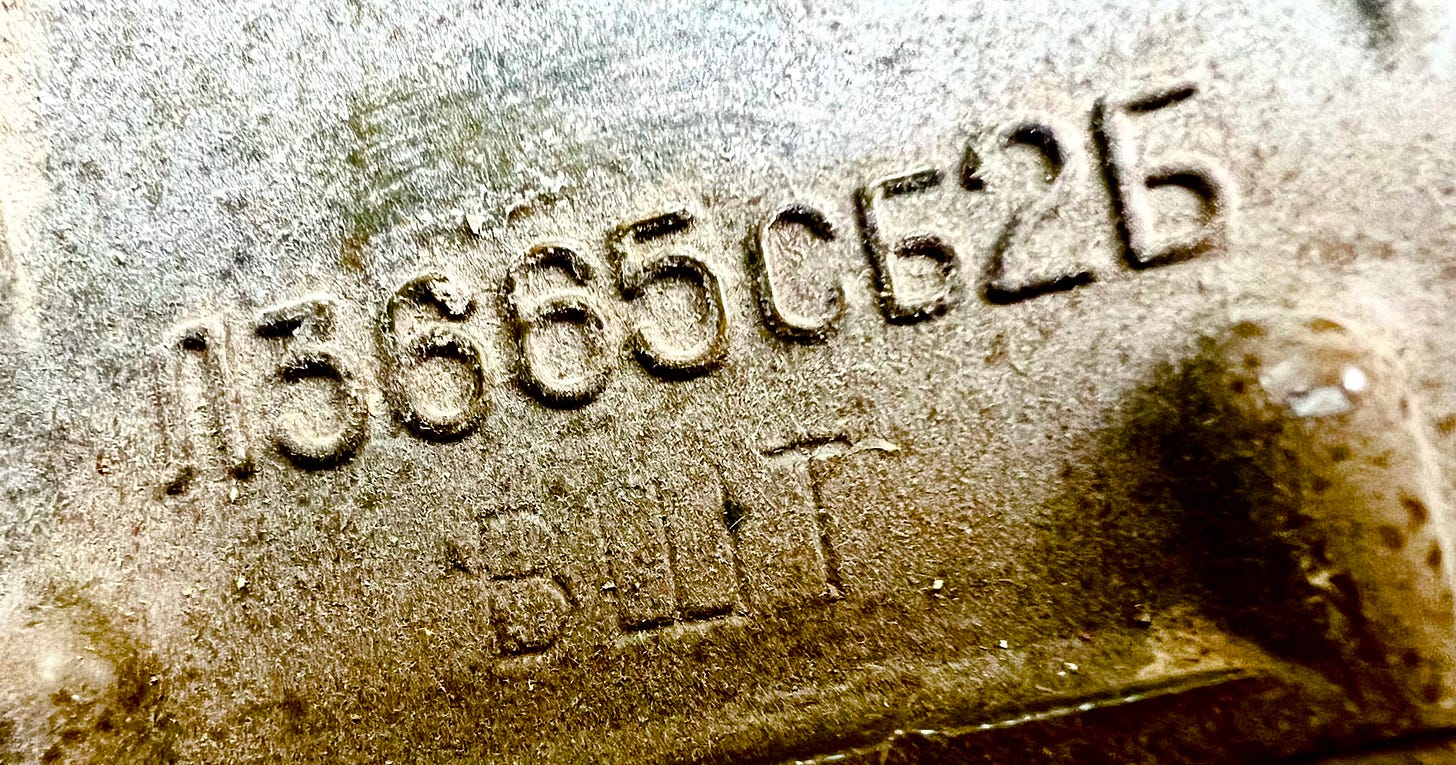

In the light of the headtorch I unroll it and am presented with three spear heads. The first is a Samburu tribal weapon that I remember buying near Lake Turkana in 1983; the second is a Dinka fishing spear that came from Lake Keilak in Sudan, but the third is the most impressive. It is a large blade, almost 40 cm long and 10 at its greatest width. Down its centre runs a strengthening rib and even after forty years in storage the point and curved sides are sharp.

Forget the Serbian thermobaric artillery shells, the multiple rocket launchers, drones and even the anti-tank missiles; for generations of Baggara tribesmen before Hemetti, for his grandfather and father, this was the ultimate and only weapon available. This is a traditional Baggara tribal spear and forty years ago it was the only weapon that men like Hemetti had available.

I weigh the item in my hand. This weapon had come from a previous journey across Kordofan Province when I'd met a local teacher and been invited to his family's summer camp. They were Baggara people and had been extremely hospitable. They invited me to ride a white bull and hold that spear. The bull, I remember, was completely docile although he did appear to have a serious frown. It was a bucolic scene of harmless fun: the people proud of their culture, appreciative of the foreigner's interest and - I admit it - convulsed with laughter at how comical he looked. The foreigner, me, full of admiration for their hospitality, their traditions and the craftsmanship that had gone into making that spear.

I replace the weapon in the newspaper and roll it up with the others. As for those shadow puppets and that Fulani stick, they remain unfound for the moment, but I hope that somewhere, far from danger and Hemetti's vile RSF thugs, those youths are still checking their looks in the little mirrors and singing songs about beautiful hair.

Fascinating stuff Kevin! I am also on a loft mission but instead of weapons ours is full of kids old cuddly toys!