It was ten minutes to five in the afternoon when I entered the cafe in a Welsh border town. There were three tables, one laden with jam jars, one in a corner, and one in the window with a view, but also two dirty tea cups. No other customers. I wanted the view. I sat down. A woman appeared, unsmiling. "If you must sit there, I'll have to do an antiseptic wipe-down."

She made this sound like a major chore. "Okay."

She sighed. "And you'll have to stand clear."

This welcome did not bode well. "What food do you have?"

"We don't have any food."

I made an excuse and walked out. I went to the only other food outlet in town, a chip shop. The Turkish owner put a few chips on a styrofoam container. "That's £3.80."

This was an expensive snack. I took out a card.

"Cash only."

I had no cash. The town had no cash machine.

Cash is disappearing fast from our lives these days. It's rare to be asked for it, even for small sums. I notice that it is the old and very young who still carry it. One of the great rituals of travel, the changing of money, is also disappearing. In much of Europe you don't ever change money, not physically, not over a counter. If you do, you're either a dinosaur or a drug dealer. In North America point-of-sale cash transactions, are predicted to fall to 6% by 2025. It’s a shame. I love banknotes with their precisely etched artwork and particular colours.

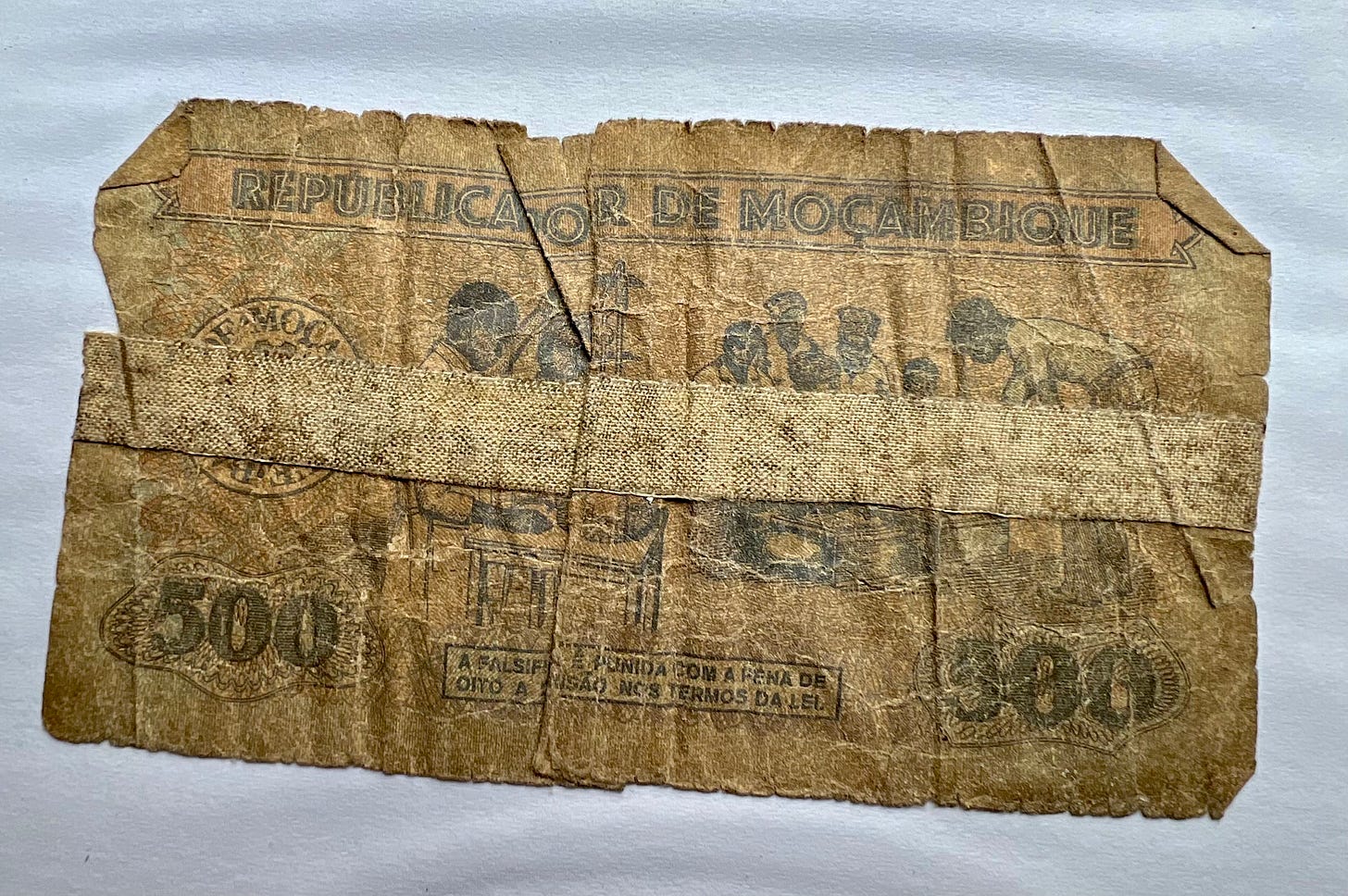

Travelling used to be all about cash. Just getting hold of the local stuff could be a significant, and perilous, part of your journey. Some countries used to demand proof of how much currency you were bringing in, and they would check it when you left, tallying it up on your official exchange form to make sure you had not gone to the black market. This was never a worry. The endemic corruption in such places usually meant that an enterprising bank official had done you a deal, and also stamped the forms.

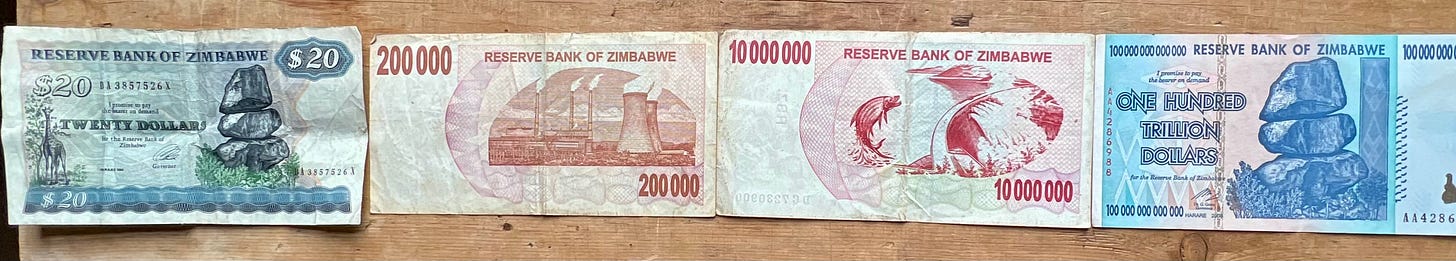

Money is all about trust. Those little rectangles of paper, with their faces and numbers, are all about reliability. Once the trust is gone, it's just poor quality toilet paper. In March 2007 when hyperinflation took hold in Zimbabwe, their dollar became almost worthless. Workers would be paid in notes that, by the time they reached the market, could not buy anything. I recall picking up $20 bills that were blowing down the street in Bulawayo, useless litter. Perhaps because money is about trust, countries plaster their dosh with the portraits of dependable individuals like George Washington, Winston Churchill and Saddam Hussein. When history cannot provide any trustworthy candidates, central banks turn to animals like the elephant or lion, or massive infrastructure projects like dams and power stations. In Guatemala they named the currency after the quetzal bird whose feathers were a valuable trade commodity in Mayan times.

In Zimbabwe, as hyperinflation gripped, the central bank struggled to find images of reliability. The $200,000 bill issued in July 2007 is almost bare on one side and has a feeble-looking power station on the other. There was also something you don't see often on a banknote: an expiry date, like they knew this was not going to end well. By the time it actually appeared on the streets, the note could purchase just one kilo of sugar. One year later they were printing a $100 trillion note with a rather baffled buffalo peering out at the bearer. In July 2008 the central bank simply slashed 10 zeroes off all bills, making the $10 billion note into a $1 bill. But hyperinflation was not so easily defeated. In November economists estimate that it hit a monthly rate of 79 billion per cent, although any sense of reality had long since disappeared. By my calculation (unreliable maths warning), that means removing your wallet in the market took sufficient time for the loaf of bread in front of you to be 300 times more expensive than when you started. At the time, the governor of Zimbabwe's central bank admitted he could not calculate the inflation rate because there was nothing to buy in the shops. A further twelve zeroes were cut. When the Zimbabwean dollar was finally abandoned, one dollar of August 2006 vintage had effectively become $10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 - 10 sextillion dollars - all of them equally worthless.

When trust starts to erode, a black market appears, like mould. At the same time, minor officials whose income is being compromised start to augment their earnings through tips and bribes. Soon the police are no better than a protection racket, their entire effort put into lining their own pockets. Genuine victims of crime get ignored, or tapped for money. In Mexico I met an agit-prop artist who had printed counterfeit 50 peso notes to give to policemen at roadblocks. The only slight addition was the small print along the base of the banknote: "Thank you for taking this worthless fake money. Your sacrifice is valued."

I took some, but never got the chance to try it out.

What will happen when trust goes down the plughole with modern finance, as it will somewhere some day? Will traffic policemen offer contactless payment into their own bank accounts? Will we be forced to hand over electronic gadgetry, or quetzal feathers at impromptu roadblocks? Will poverty and hunger among minor officials rise rapidly as they fail to establish alternative methods of renumeration, followed rapidly by riots and sudden catastrophic changes in government? Or will our cards simply stop working, forcing us to rootle down the back of the sofa and find some coins?

Burma, July 1988.

Almost as soon as we emerged from airport customs, they were on to us like sharks on to sardines. Some visitors had not been warned and got scared. I'd been told this would happen and yet it was still a shock. A gang of men running towards us, their right hands up in the air and two fingers dangling and waggling. An Australian woman, towering over them, started laughing. "Holy shit! I get it. They want Johnny Walker. They want whisky!"

I had been told in Thailand, before I boarded the flight to Burma. Buy a bottle of Red Label in duty-free. Sell it at Rangoon Airport. Pay for your trip.

I held up the bag. A man in a grubby sarong shoved a wad of banknotes in my hand and grabbed the bag. I made him wait while I counted. It was a slow process and required care. One year earlier the government of dictator, Ne Win, had summarily withdrawn the 25, 35 and 75 kyat banknotes. It happened on a Saturday morning at 11am when people were heading to market to buy food. The three most common banknotes, it was announced over loud hailers, were no longer legal tender. Just like that. People went into shock. Not only could they not buy food, their savings were wiped out.

Why, you might well ask, would a country have 25, 35 and 75 value banknotes in the first place? The short answer is that the 50 and 100 notes had been withdrawn suddenly in 1985 to be replaced by a 75 note that 'celebrated' the 75th birthday of Ne Win. The 15 and 35 denominations soon followed. Little or no compensation was offered. Two years later the 75 was gone, not replaced by a 77 - try not to be too logical here - but by 45 and 90. These were General Ne Win's favourite numbers because they incorporated multiples of nine. Why nine was his favourite I'm not sure - perhaps it was the age he left school.

The new banknotes were emblazoned with colonial era heroes; the old notes had born the image of General Aung San, but he was definitely no longer a favourite of Ne Win. His daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi, was now Ne Win's rival.

Now armed with a good bundle of 90 kyat notes, I set off into Burma. In the once-plush colonial hangout, The Strand Hotel, I drank gin (sorry, sir, no tonic) and watched the cockroaches scuttle across the bar. Next day I caught the train north and visited Lake Inlé. A few days later in the small town of Taunggyi, I walked through the market. It seemed very quiet. I fell into conversation with an old lady who was a piano teacher. "Terrible things are happening in Rangoon," she told me. Her son, a student, had gone out to protest that he could no longer afford to eat. Soldiers had grabbed a friend of his and smashed his head open on a kerbstone. He died in the street.

The kyat was plummeting and in some exchanges I'd carelessly allowed a few 75 and 25 kyat notes to be palmed off on me. As they were useless, I needed more cash. A shady money dealer took me to one side and offered to buy US dollar bills. He would pay me a kyat commission to give him a clean new $100 bill in exchange for ten filthy old $10 bills. These new kyat paid for a seat in a shared taxi across country to see the ancient temple complex at Pagan. The vehicle was a World War II Willys jeep and somehow the driver managed to load 26 people on it. The gear lever had long since broken off and been replaced with a length of timber with which he had to smash at the gears until they slotted into position. The rain became relentless. Would we crash, drown or go bust?

After Pagan I needed only sufficient money to get to Rangoon Airport, but all I had was ten grubby US dollar bills and several 75 kyat notes. No one would accept them. Fortunately, the driver was flexible. Did I have...? He made the walking fingers gesture. No. But a tee-shirt emblazoned with the word Guinness would do.

The day after I left, Ne Win resigned, but appointed an unpopular and brutal soldier, Sein Lwin, as his successor. He lasted 17 days. Pro-democracy protests ended in a military crackdown and takeover on September 18. A decade of liberalisation began in 2011 but was curtailed by another coup d'état in 2021. Today Myanmar is in a state of civil war with the military junta using air power to counter a growing popular uprising. The planes and helicopters are supplied by Russia and China. India is also supplying weapons. The kyat is officially trading at about 2,000 to the US dollar although the black market rate is probably 50% higher. General Aung San has been restored to the new 1,000 kyat banknote.

Quiz part two next week, and answers to part one.

Top Row [? - Soviet : Lenin - British : Victoria or Elizabeth - Iran : Khomeini - ?]

Bottom Row [? - ? - ? - ? - ? - India : Gandhi - China : Mao]