Are you fed up with all the climate bad news? Me too. But not as much as I’m fed up about governments doing nothing about it. My horrible, sneaking suspicion is that nothing significant will be done until something cataclysmic happens, by which time it will be a bit late. So here today, a personal allegory from a trip to Papua New Guinea in 2017.

The day starts well. There is a blue sky, a little wind, but not too much. I help carry the diving gear down from the store to the jetty and load the boat. Two air tanks each for each diver. There are four of us.

Some people love diving. They like the equipment and the knowledge required to use it correctly. I'm not like that. What I like is wildlife and if it happens to be underwater, then I'm prepared to zip myself into all that annoying neoprene, strap on all the heavy apparatus and descend, just to see what's there. I find all the kit, and all the calculations a tedious necessity.

We motor down the fjord, watching formations of parrots fly high over the jungle-clad banks. This is Papua New Guinea and we are heading out to the area where Jacques Cousteau had made his last dive. It's a kind of homage to the great man.

I learned diving in a swimming pool when I was a schoolboy. It was unusual, I'm sure, to get that kind of opportunity at a British state comprehensive in the early 1970s, but Miss Perry the art teacher was into Scuba diving and formed a little club that met at lunchtimes. I was a Jacques Cousteau fan and I had the minimum requirement, the Lifesavers Bronze Award, so I was allowed to join. My first mask was a leaky secondhand thing and the snorkel was a tough old brute that squeaked against my teeth. I couldn't afford fins. Only boys went along, some merely to sneak a peek at Miss Perry's generous bosom. She always wore a wetsuit and weight belt which we joked was particularly heavy in order to sink her chest. We never let Miss Perry hear those jokes, however, she was a formidable character.

We learned the basics: how to dive below the surface, how to clear your mask underwater and how to rise up, blowing gently into the snorkel so that you could breathe again quickly once up. We learned signals and rescue drills. When we had mastered all that, she brought in an air tank and we started learning about pressure and air consumption. Miss Perry always said, "Relax underwater. Don't work too hard. If you get excited, or strain to go faster, you use more air. Scuba is not like snorkelling. Scuba is meditation." It was the first time I ever heard that word.

The sea is rough when we get past the coastal reef, but the divemaster is not worried. The plan is to get out to a huge coral tower that rises from extreme depth, then we will drop in on top and explore a bit. The depth will be about 12 metres, he explains, using a map. "We'll come to the drop here.” He means the cliff wall. “Then we’ll descend to 20 metres then make our way along the wall. There'll be some sharks - nothing dangerous. Watch out for a possible current here. There's sometimes a severe rip, but today should be fine." He goes through the signals for various creatures.

I try and memorise the map, check my regulators and tank gauges, then when it is my turn, roll off the boat.

The transition from being a land creature to a marine animal is always something I relish. The sudden change in sound. Gone are the voices, the boat noise and the wind, replaced by the rasp of your own breathing and the sudden cold blue intimacy of the water. Down at 12 metres there were the reef noises: clicks and clacks of fish. We group up and set off. I tuck my hands close to my chest, fin with the gentle regular beat that requires no effort. The coral is healthy which is good to see. When the sea heats up, corals can get bleached and die, something that has been happening on Australia's Great Barrier Reef, but not here. I see huge dark red fan corals, vast schools of fish, and the gape of giant clams which look like star-spangled velvet. Inside the soft lemony tentacles of anenomes are brilliant orange clown fish, one large and several small. Once these fish have adopted an anenome they stay all their lives, slowly working their way up the heirarchy until, with some luck, they reach the top. On that journey they change sex.

We reach the edge of the mount and I look down into the abyss, a deep dizzying darkness where sharks cruise. Flotillas of brightly coloured fish drift off the wall, then suddenly move in, like the entire coral mountain is exhaling, then inhaling. And it is, in a way, the whole vast structure is alive.

Working my way down the wall is a slow process because there is so much to see: sponges and corals, then the sudden gruesome face of a moray eel glaring out at me. A turtle spots me and after a moment's hesitation, takes off. I stop to closely admire several nudibranchs, a marine slug. There are two of pure bright blue with orange spots, then another creamy one with feathery external gills. I move close and see a movement in a deep recess, an octopus staring out at me, its body tense and bunched. Then it squeezes out a hole and with wonderful agility whips around a corner. I follow and watch it for a while. Then, magically, in full view, it is gone, changing colour and texture.

When I look around I realise I have fallen behind a bit, descending too deep in my pursuit of the octopus. Even a few metres can add to your oxygen consumption. I glance at the tank gauge. I'm using too much. Slow down. Steady. The excitement of seeing so many fabulous creatures has lured me into breathing quickly. I ascend slightly and catch up with the group who have paused. The divemaster signals. This is where we might encounter a current. He leads off around a coral buttress.

As soon as I follow, I understand that something is wrong. The current is much more powerful than any of us expected. It pushes me off the buttress and outwards. I start finning hard, make it back to the cliff. Now I am slightly sheltered, but I cannot hold on to anything. Everything on a reef is sharp. My diving buddy has gloves and is using both hands to haul himself forwards, but I cannot. I have to fin, but I'm not making any progress. I’m going backwards. Rising within me I feel a shadow of panic, like the glimpse of a dangerous creature in the darkness, something to be feared. I force myself to relax. I will not look at that monster.

The water is turbid, filled with tiny particles, and visibility is suddenly cut from several metres to three or four. My buddy spots my problem and removes one glove for me, then disappears around the corner. For a desperate few seconds I struggle to hold position and sort out the glove. It is all tangled in itself. Some fingers in, some are out. It takes an age to get it on. By the time I've managed that, I'm alone. And then the oxygen runs out.

When we were in the school swimming pool, we would hold competitions to see who could go without air the longest. I was always quite good at it. With practise I learned that I could get to three minutes. But there is one vital difference. When you know you are going to have to hold your breath, you breathe in first. When the oxygen in your tank runs out, it does so without warning and on the exhalation. One second you are breathing in, the next moment, lungs empty, you try to inhale and there is nothing. It is like that moment when, descending familiar stairs in the dark, you step confidently off the last one and realise you have miscalculated. There are more. And at that precise moment, an invisible horse kicks you in the diaphragm.

I know immediately what I have only a few seconds to do. I must catch up. With a massive wrench of the left arm, I throw myself forwards, finning hard. I round the corner and go after the other divers. Another buttress. A single thought cracks through me. Too fast. This is happening too fast. I have no time. Time is up.

In a gully just around the buttress, I spot them. I grab the divemaster's fin and made the cut-throat sign: NO AIR. I reach for his spare yellow regulator and miss.

He pulls my own useless regulator from my mouth and inserts the spare. I'll never forget that first desperate suck of oxygen. It was the best one. It was heaven.

On the boat later, I feel deliriously happy. My eyes are full of tears. Life is wonderful. As we smack across the waves I'm singing Big Yellow Taxi:

"Dont it always seem to go,

That you don't know what you've got till it's gone."

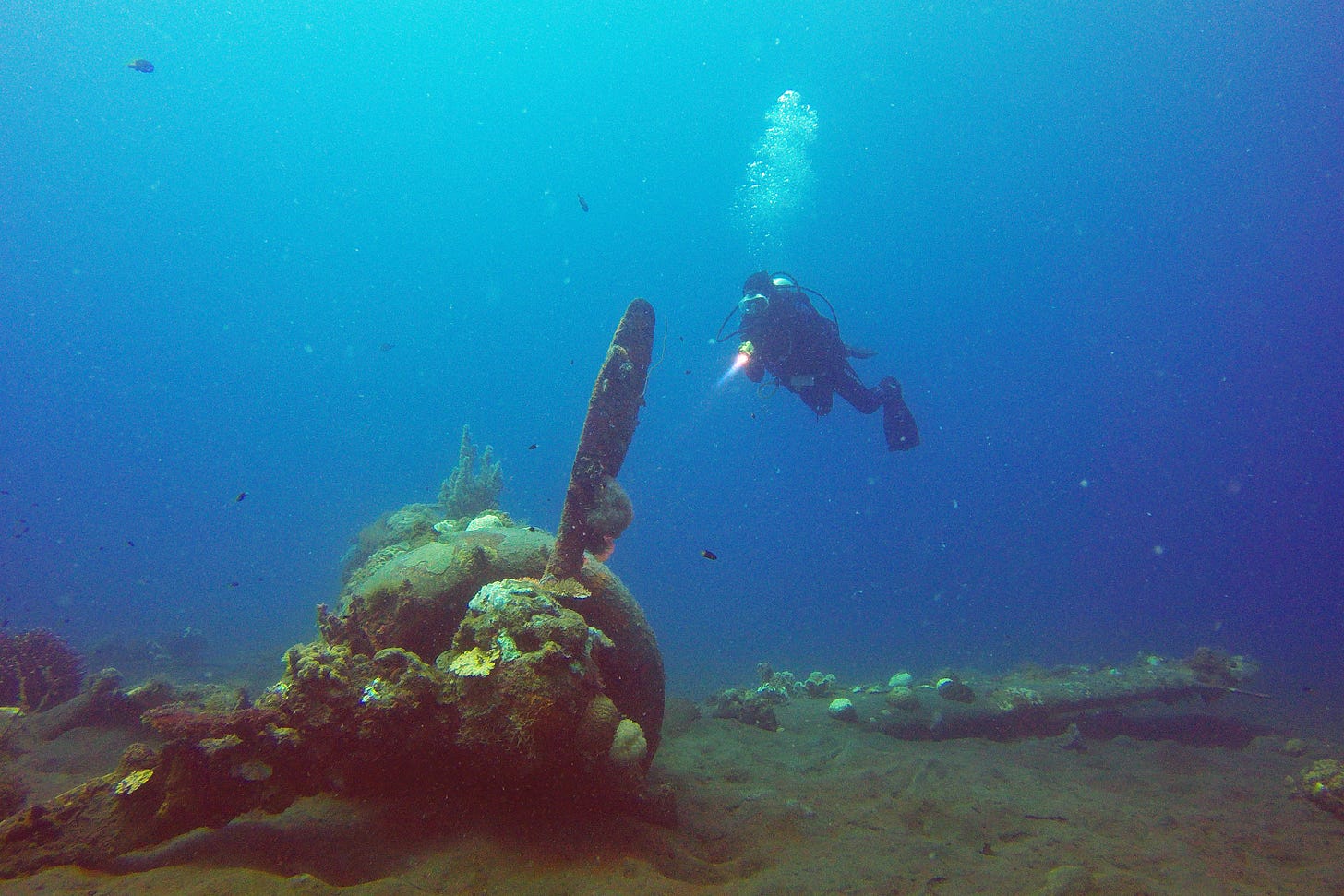

An hour later I do a second dive, this time on a WWII Japanese fighter plane. I check my gauge frequently.

next week: the rest of the story!

That sounds terrifying Kevin!

Berloody hell!